Voices from the Vault: Principal Sir James Irvine

In October 2006 we received the first installment of the papers of Sir James Irvine (UYUY250/Irvine), from Julia Melvin, his granddaughter and biographer. Professor Irvine was Principal of the University from 1921-1952 and is considered by some to be the ‘second founder’ of the University due to his work in revitalising the University’s community, buildings and academic reputation.

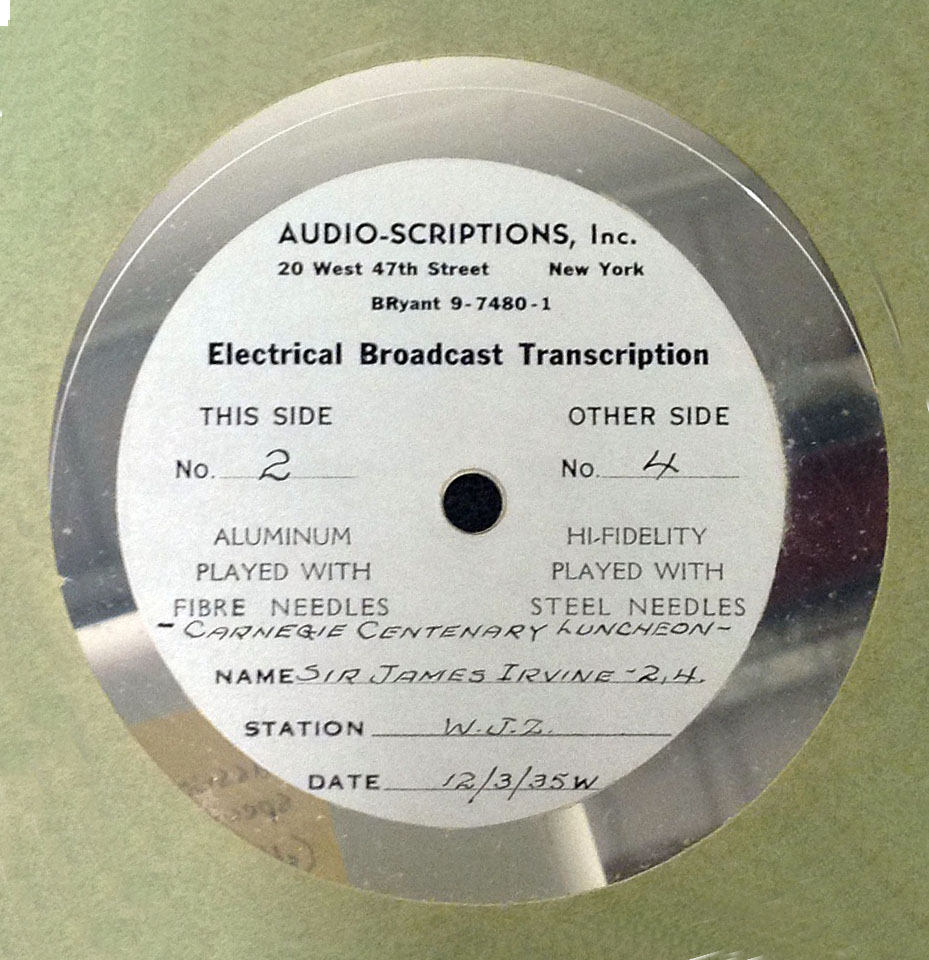

Most of the collection exists in the traditional formats one might expect of a 20th century archive – hand-written papers, typescripts, printing, photographs etc. However there was a box with more unusual contents –four 12-inch aluminium discs.

Fortunately the discs have some useful descriptive information written on the label – archivists aren’t always so lucky! We know that they were created on 3 December 1935 (12/3/35 in American-style dating) from a broadcast of the Carnegie Centenary Luncheon, from a radio station with the call-sign W.J.Z. They were produced by Audio-Scriptions Inc, a company based in Manhattan that created recordings of radio broadcasts in a manner analogous to a newspaper clipping service.

A little research revealed that bare aluminium discs were once used for one-off recordings. Introduced in the late 1920s, they saw a modest adoption in the 1930s both in radio as transcription discs used for capturing events and sponsor spots, in coin-operated “record-your-voice” booths, and amateur recording studios. Already on their way out by the early 1940s, many of these discs were melted down in World War II scrap metal drives.

We finally decided to tackle their digitisation this year, having sought advice from Peter Adamson, a retired member of IT staff and an expert in historic recordings, and our Media Services department. Peter told us that aluminium discs can be irreparably damaged when played with a conventional stylus, and that we needed an experienced audiovisual expert with suitable equipment; we asked Adrian Tuddenham at Poppy Records, who has played and digitised similar discs before, for his help.

Adrian explains the digitisation process:

“The disc slipped when it was just resting on the turntable, so it had to be held down with a brass weight. Under the weight is a paper stroboscope to help set the exact speed of the turntable.

The recordings had been made on alternate turntables which were not accurately speed matched. The grooves on aluminium discs are embossed, not cut, which puts a heavy drag on the turntable during the recording process. When the embosser is at the outside edge of the disc, the drag can be sufficient to slow down the turntable, resulting in a noticeable change of pitch at the start of each disc when compared with the end of the previous one.

Because of this, the disc speeds had to be matched by listening to the end of the digitised recording of the previous disc and matching the new one’s speed to it. As the disc played, the speed had to be gradually increased so as to keep the pitch constant; by the end of each side, the speed had to be exactly 78 rpm.

The overall playing time was very important to American commercial broadcasters and it provided a useful check that the speed correction had been done accurately. The running time of the entire transcription was 30’20” – but there was 20 seconds of announcement at the start, so the programme time was exactly 30 minutes.

The embossing system also suffers from very bad high frequency loss caused by slew-rate limiting at the slower surface speed found at the end of each side. To reduce the audible jolt which this produced at the changeover point, the incoming disc was heavily filtered so as to give a similar sound, the filtering then being gradually reduced to restore the maximum available bandwidth.

The embossing process causes the material squeezed out of the groove to be thrown up into ‘horns’ on each side. The playback stylus can easily drop into the land between the horns of adjacent grooves and become trapped there, playing a noisy and distorted rendering of two grooves simultaneously. This is sometimes quite difficult to avoid at the beginning of each side, and several false starts may have to be made before the stylus drops into the groove correctly.”

Once the discs and digital recording were returned, we were able to fill out our previously thin catalogue record for them. Veronica Whymant provided us with a full transcription – really the best way of describing recorded speech to library users! You can now listen to the digitised recording, and read the transcription, on our digital collections portal.

Once the discs and digital recording were returned, we were able to fill out our previously thin catalogue record for them. Veronica Whymant provided us with a full transcription – really the best way of describing recorded speech to library users! You can now listen to the digitised recording, and read the transcription, on our digital collections portal.

We learned from the transcription that the speech was made at the Andrew Carnegie luncheon of the English-speaking Union of the United States of America, and that other speakers that day included Louise Whitfield Carnegie (Andrew Carnegie’s widow) and Sir Gerald Campbell, then British Consul General in New York. The event was introduced by Arthur W. Page Vice President of AT&T, and public relations guru.

Early listeners of the record have already enjoyed what appears to be the only surviving example of Principal Irvine’s voice – he was clearly a highly accomplished public speaker, and was regarded so at the time. Of another speech of Irvine’s, GK Menzies, Secretary of the Royal Society of Arts, said

“I can honestly say I never heard a more finished piece of oratory, nor one that moved me so profoundly…”

It’s also an interesting example of a “professional class” Scottish accent of the period, probably barely distinguishable from a modern Radio Four newsreader-style accent to many. It certainly doesn’t correlate with Lady Cynthia Asquith’s description of Irvine’s voice as ‘Scottish as Peat’, after she met him at J.M. Barrie’s Rectorial Installation in 1922.

The brief speeches by Mrs Carnegie and Sir Gerald Campbell are also fine additions to the archive. Louise Carnegie’s message of international cooperation fits neatly with Irvine’s message, and Sir Gerald’s amusing, bluff, and slightly nonsensical speech shows why he was so highly sought after on the after-dinner circuit in the States.

Though the views expressed by Irvine in the address are in many ways of their time, the value he places on the international exchange of educational opportunities, and his gratitude for the role of benefactors in supporting education through scholarships, remain highly relevant to our modern University. Irvine personally benefited from benefactions as an 1851 Exhibition Scholar and as the first Carnegie Research Fellow, and it is in his name that the Irvine Scholarship in Chemistry, established in his honour by his granddaughter Julia Melvin, continues this legacy today.

Sean Rippington

Digital Archives Officer

[…] part of our occasional audio-visual blog series, this week we look at (and listen to!) the Tullis Russell brass band, which celebrates its 100th […]

[…] attended the centenary celebrations of Andrew Carnegie in New York in November 1935 (see an earlier blog post on the recording of Irvine’s speech). […]