Finding Phillis: The First African American Author

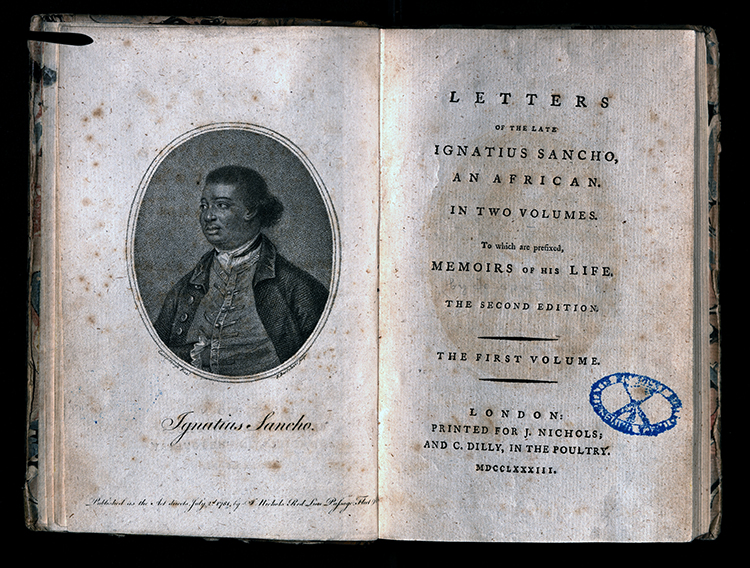

This year is the 250th anniversary of Phillis Wheatley’s work Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, the first volume published by an African American woman in English. Despite racial prejudice, Phillis’s book was a significant testament to the genius of her poetry. Her works were a proof of her own understanding of her identity and reveal her strength to go against circumstances that would have made it easy to suppress her voice. I have been involved in the research for an online and physical exhibition of Phillis’s works at St Andrews, and this blog is part of a wider project to celebrate the book’s publication. The St Andrews Library copy has been in the collection since 1773 and is currently displayed in Gallery 2 of the Wardlaw Museum. Accompanying it are two more books from St Andrews own rare books collection, The Letters of Ignatius Sancho, An African and Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia, both offering contrasting opinions on Phillis’s work.

Phillis’s talents in poetry became part of a wider discussion on the question of racial superiority and inferiority. Her skills as a writer were judged in contrast to her status as a Black enslaved person. As seen in Jefferson’s Notes, he claimed “the compositions published under her name are below the dignity of criticism.” Phillis was likely to have been perceived as an enslaved person before she was judged as a writer of her own merit.

The book itself contained a list of prominent men in Boston, who all verified that the poems were in fact written by Phillis.

It is important to recognise the challenges Phillis had to face to have her book published in the first place. The initial proposal for her book failed to get enough publicity in America, before it was sponsored by Selina Hastings (the Countess of Huntingdon) and published in London. Celebrating Phillis’s work is important because it should not have been necessary for Black or enslaved peoples to write and publish works of art to justify their humanity. In contrast to Jefferson, Sancho states in his Letters, “Phyllis’s poems do credit to nature – and put art- merely as art – to the blush.”

The 250th anniversary of the book acts as an important milestone in the history of African American writers. Phillis continues to be an inspiration for generations of Black poets. June Jordan’s The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America and Drea Brown’s award-winning dear girl: a reckoning both re-imagine Phillis’s experiences as a young child and growing up as a slave with the Wheatley family. Such works explore the complexities in how the family that helped Phillis communicate her voice as a poet was part of the system that deprived her of her freedom and identity from a very young age. Phillis’s message of freedom and desire for harmony continues to echo, seen especially in ‘Hymn to Humanity.’ Phillis continues to be relevant because her works are part of a legacy of overcoming prejudice and suppression of Black and minoritized voices.

Working on this project honours Phillis’s legacy and continued impact on the literary scene. A year ago, the name Phillis Wheatley held no significance to me. After working on this project, I have been on my own journey of discovering Phillis for myself. From reading her poetry, biographical accounts of her life and reading the letters of her long-lasting friendships, to me, Phillis is an exceptional example of a resilient character rising against her circumstances.

Phillis’s impact cannot be limited to the Americas, as seen in St Andrews receiving a copy of her book in 1773. New works and research continue to be attributed to Phillis and her life. Phillis was more than a writer. She was deeply involved in her community and her connections allowed her to thrive despite the restrictions placed on her as an enslaved servant. Accompanying the physical display of Phillis’s work at the Wardlaw Museum, is an online exhibition discussing details of the St Andrews copy and its history. Further events are occurring for Black History Month, such as a Critical Conversations event taking place on the 10th of October on Teams Live, and a reception for the book in the Wardlaw Museum on the 26th of October. As we celebrate the anniversary of the publication of her work, I hope that this blog will inspire people to also find Phillis for themselves.

Jahzel Asi

Undergraduate Research Intern, School of English

The case of Phyllis Wheatley is interesting. John Louis Gates Jr has some interesting observations about it in the editorial to the Journal 'Critical Enquiry' Vol.12 No.1 in 1985. The "liberal"-minded gentlemen who sponsored Phyllis attested the following in a preface to her book: "We whose Names are underwritten, do assure the World, that the poems specified in the following Page, were (as we veribly believe) written by Phillis, a young Negro Girl, who was but a few Years since, brought an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa, and has ever since been, and now is, under the Disadvantage of serving as a Slave in a Family in this Town. She has been examined by some of the best judges, and is thought qualified to write them." The irony is that the idea that literacy proves intelligence is a product of the already-literate, white, European/American culture, which is blind to the fact that if Phyllis had never learned English, nor learned to read and write, nor ever wrote poetry, she would still be as intelligent as anyone who did. For all its good intentions, it is based on a racist assumption.

Reply from Professor Tom Jones: These are important topics that scholars of Phillis Wheatley are thinking about a lot at the moment. Some scholars are trying to move away from the idea that Wheatley was subjected to a test by the Boston gentlemen named in the prefatory material to her book. Instead they suggest that she was actively soliciting support from a group of like-minded people for the publication - she was the active person. Some scholars have also asked whether we ought to think more about oral, musical and other forms of expression - slave songs, in particular - when we think of the origins of African American poetry. In exhibiting and discussing Wheatley’s book we hope we can celebrate this major achievement in print culture as part of a broader appreciation of African American cultural expression, in all its forms.