52 Weeks of Inspiring Illustrations, Week 18: the Catesby Conundrum

On 23 April 1712, a young Mark Catesby landed on the shores of Virginia seeking out new animals and plants that were not native to England and there he remained for seven years. Catesby sent back a few specimens and observations to well-known botanist William Sherard who encouraged Catesby to consider publishing his observations and illustrations.

After three years of gathering support back home in London, Catesby left again for the New World in 1722, this time for the Province of Carolina. He set up home in Charlestown and during this stay Catesby enlisted the help of Native guides to take him further upcountry and into the mountains where he first encountered bears, buffaloes and panthers. His main focus was the observation and collection of specimens of trees and shrubs, but certainly the wildlife had an influence on Catesby. During this trip he sent his observations and specimens both to Sherard and Sir Hans Sloane. Catesby also visited Florida, Jamaica and the Bahama Islands.

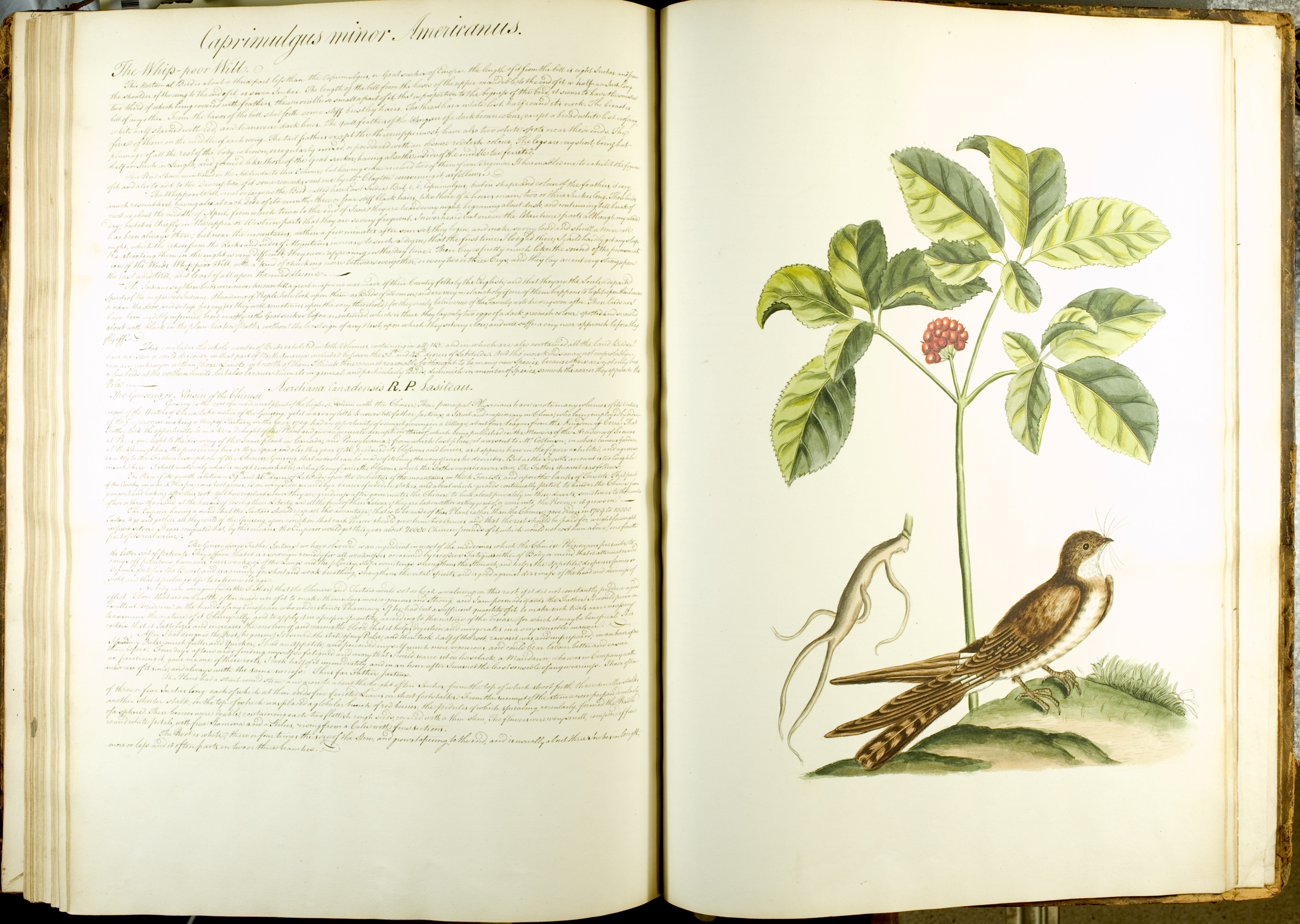

Catesby returned to London in 1726 and set to the task of editing his observations and illustrations into what would be his The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, a task which would take over 19 years to complete. This is considered to be the first published account of the flora and fauna of North America. Catesby’s first task was to find the best way to reproduce his paintings for the print medium, he approached painter Joseph Goupy for advice and taught himself how to create engravings, stating in his preface:

“I undertook and was initiated in the way of etching them myself, which, tho’ I may not have done in a grave-like manner, choosing rather to omit their method of cross-hatching, and to follow the humour of the feathers, which is more laborious and I hope has proved more to the purpose.”

-p. xi, v. 1 of Catesby’s The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands

The cost of such a large-format production was daunting for Catesby and so it was financed by an interest-free loan from Peter Collinson, a fellow of the Royal Society. The first volume of his Natural history was published in 1731 and was received so well that he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1733. The second volume of this work was published in 1743, and by 1748 an appendix to the first volume (adding 20 more plates), Catesby’s Account of Carolina and the Bahama Islands and a map had been published. In total, this two volume set contains 220 engraved and coloured plates of the highest quality and one folded map. His work influenced the great naturalists of the time, including Linnaeus and Banks. Catesby is often overshadowed by his 19th century descendants Audubon and Gould, however he is widely recognised as being one of the first people to describe bird migration and the quality of his art work speaks for itself.

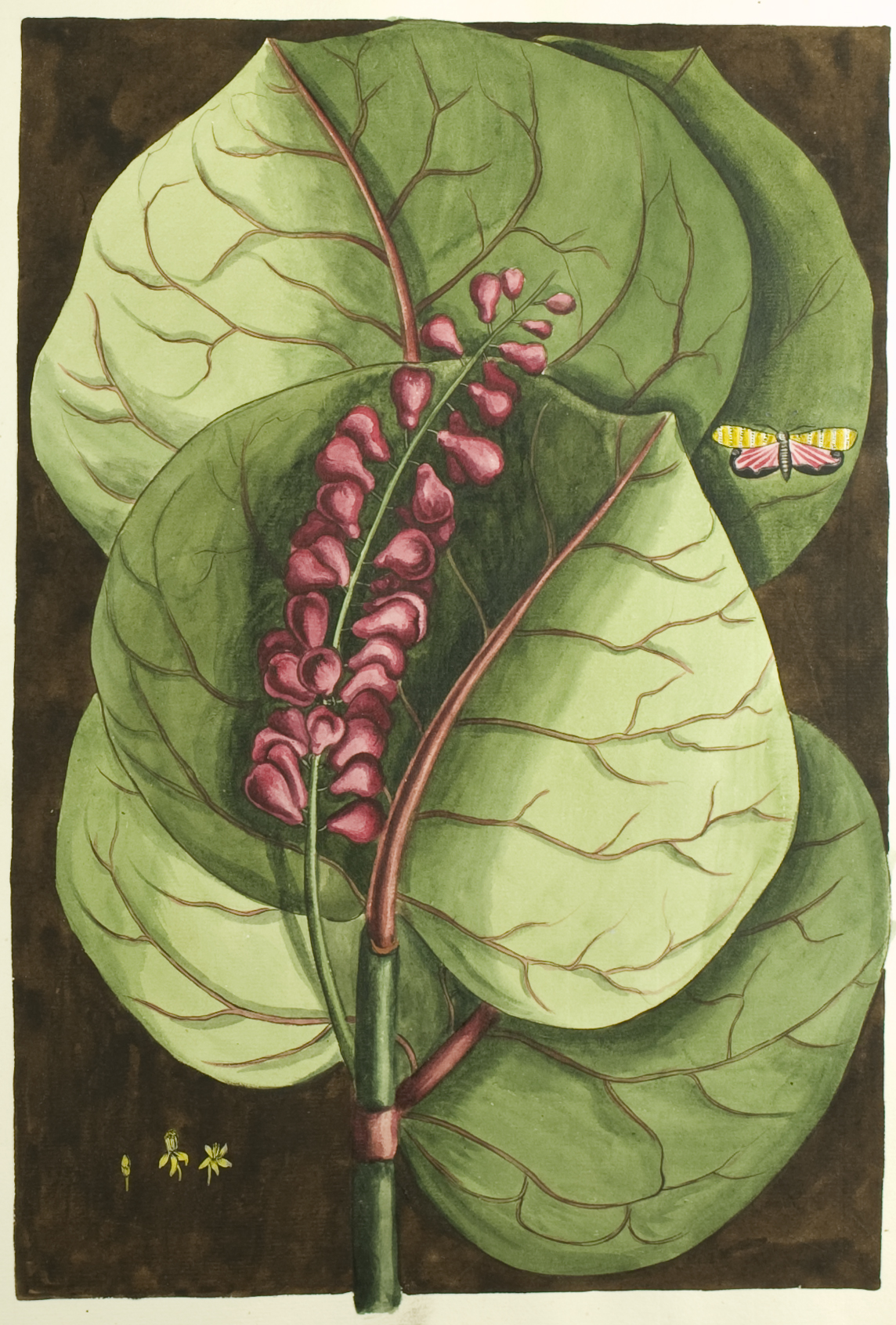

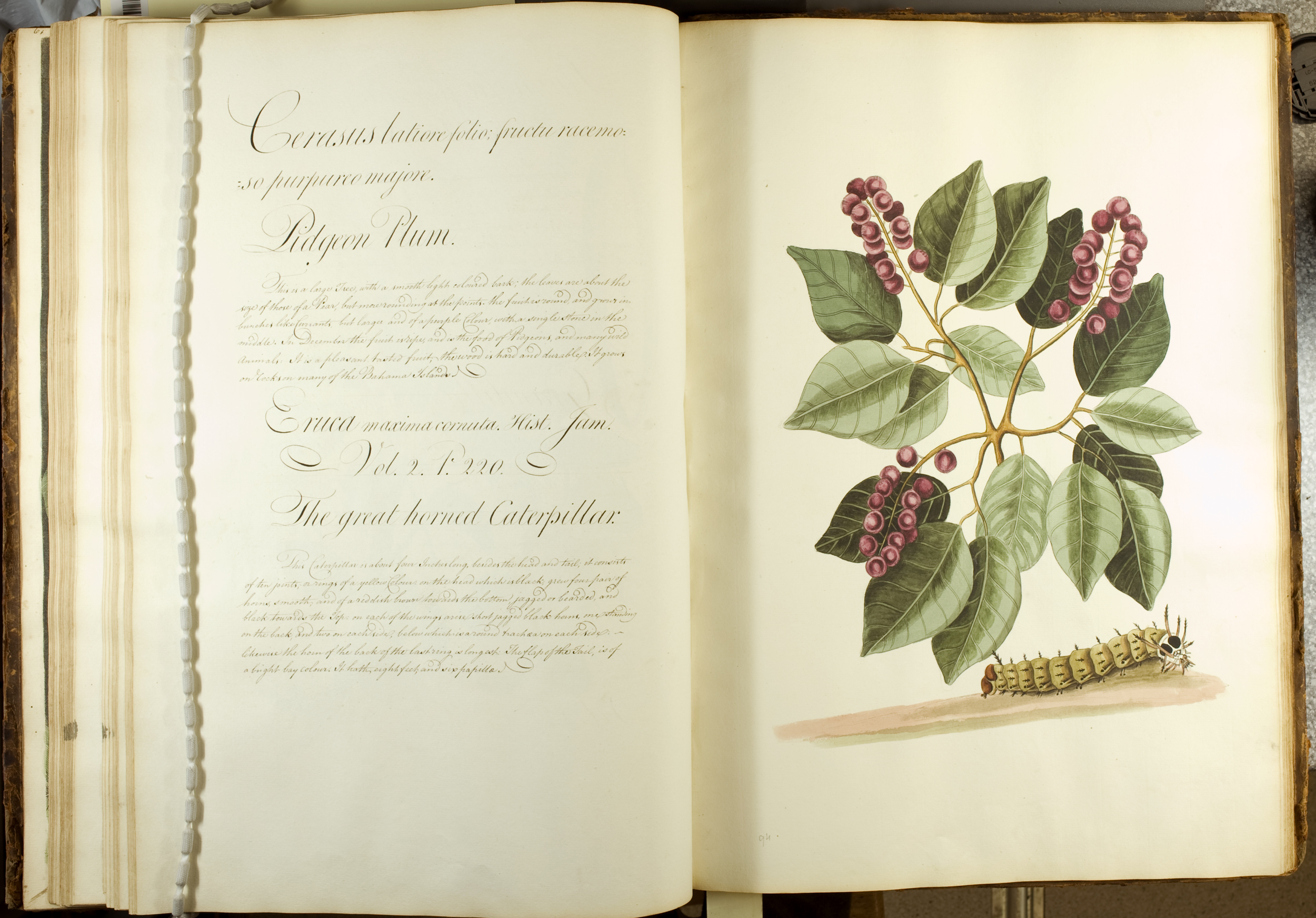

These two volumes have been scanned and are available online via many resources, however the copy of Catesby’s The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands held by St Andrews provides us with this week’s illustrations. This copy has its own story to tell: the last 20 plates and pages of volume 2, and the 20 plates and pages that make up the Appendix for volume 1 are missing. Yet, instead of being a total loss, these plates have been replaced with fantastic watercolour copies of the plates and the English text has been supplied in a clean, 18th century copper plate hand.

The quality of these watercolours when compared to the original plates is astounding. For a time it was suspected that these actually could have been Catesby’s originals, however this isn’t possible because Catesby’s widow sold his original watercolours to George III in 1768 (now part of the Royal Collection). The English text supplied is also verbatim of what appears in the printed volumes. The copyist must have been working from the plates and printed volume, as there are only very minor differences that can be detected. For example: in the plate of the ‘Great Horned Catterpillar’ there are 15 grapes on the lower left-hand bunch, whereas in the watercolour in St Andrews’ copy there are only 14 (see above).

This is a strange puzzle to work out, as both volumes have an index which was issued before the 1748 three-language index (English, French and Latin). Also, the 20 leaves of plates and 20 pages of letterpress that make up the Appendix have been reproduced in watercolour at the end of volume 2. We do know that the University purchased this set in 1782, however there is no indication in the books or in our records as to who might be responsible for the manuscript and gorgeous watercolours.

Whatever the case may be, these watercolours add a new inspiring twist on St Andrews’ copy of this lovely set of books.

–DG