52 Weeks of Historical How-To’s: Week 20, Iron Gall Ink

When the idea for the 52 weeks of Historical How-To’s came to light I thought it made sense to explore the subject of ink. From manuscripts to books, and even photography, ink is present extensively throughout the collections to convey text and images.

My first thought went to iron gall ink, an interest brought out by discussing some of its harmful effects over manuscripts during my preservation lectures. With the contributions from Rachel Nordstrom and Eddie Martin we also thought it would be nice to complement the ink manufacture with some prescriptions existent in our collections.

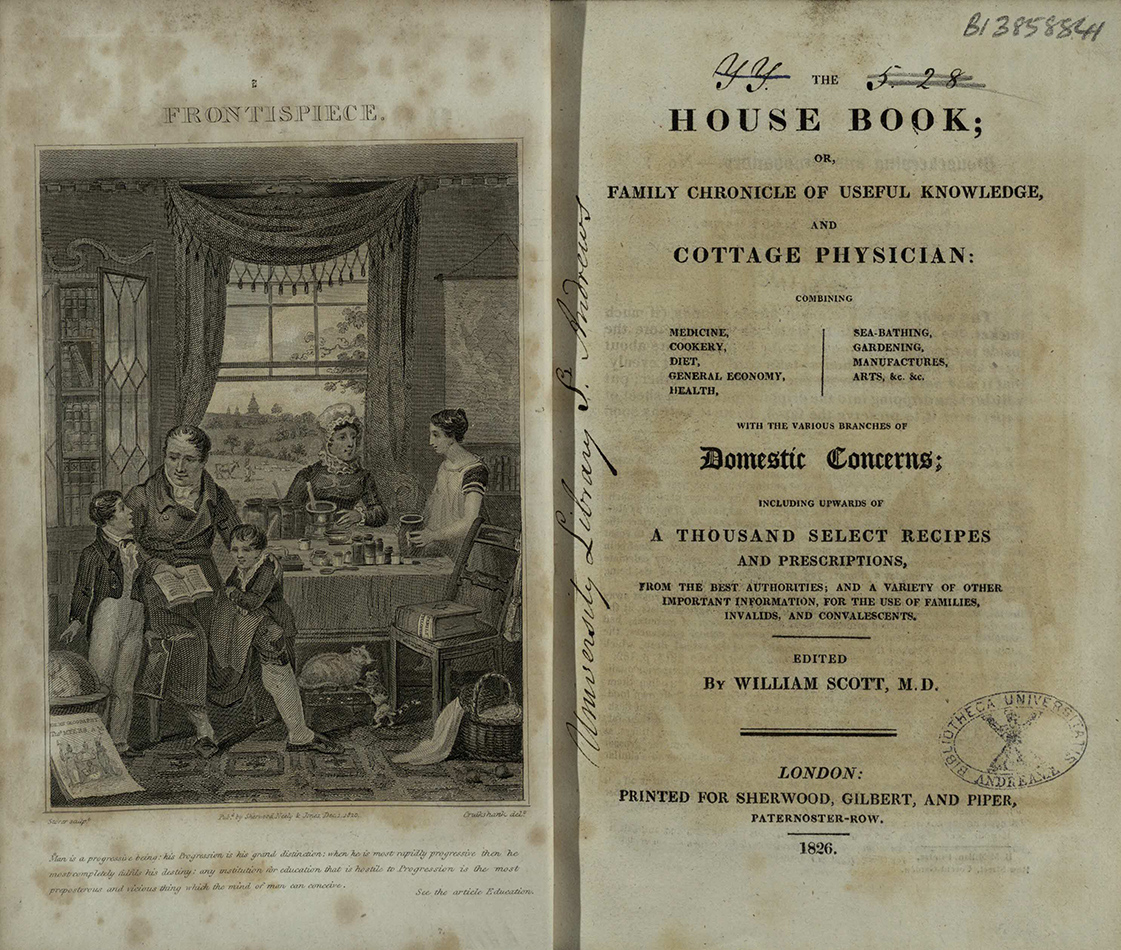

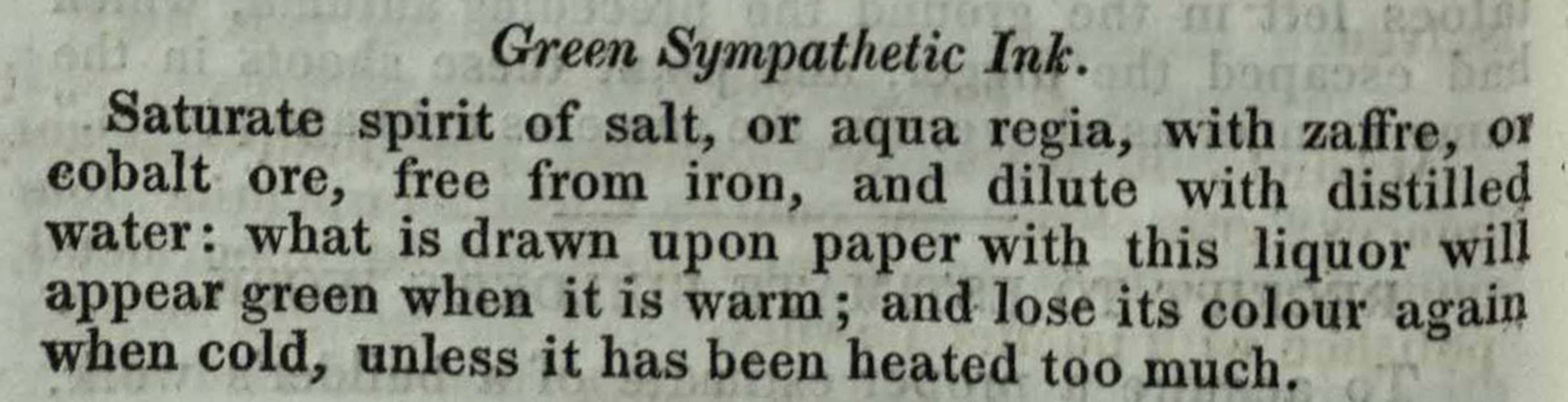

Thanks to Briony Aitchinson we were able to locate some examples of more recent instructions. The House Book (1826) edited by William Scott contains an assortment of recommendations, recipes and prescriptions for domestic use. An example is this recipe for Green Sympathetic Ink which contains among its ingredients aqua regia, a highly corrosive substance able to dissolve precious metals such as gold. A careful examination of the ingredients within the recipes made us realize it wouldn’t be safe to venture into their making.

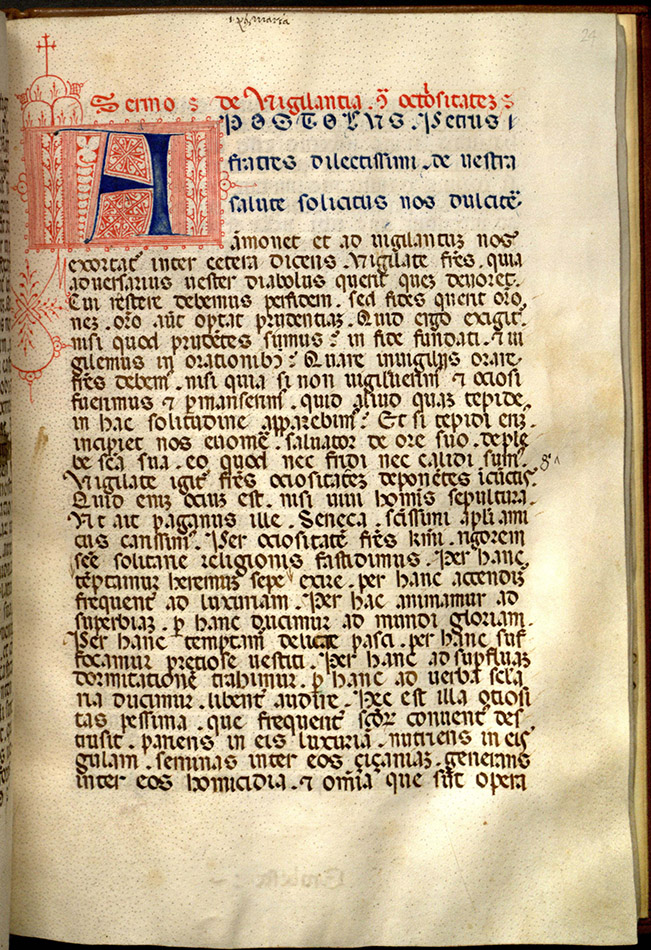

Iron gall ink origins are not clear, but according to the book Forty Centuries of Ink it was already known to Romans and Greeks. During the dark ages until the 12th century, formulae for the making of this sort of ink were transmitted by monks, first orally and later compiled into “Secretas” (a type of instruction book circulated between monks). Ingredients mentioned included sour galls, Allepo galls, green and blue vitriol among others. In the 12th century Iron gall ink became the predominant ink for writing due to its high penetration in paper and, unlike carbon ink, it didn’t fade over time.

Iron gall ink is produced by the combination of tannins (in this case present in oak apples infected by gall wasps) with iron sulphate using a liquid such as water or wine as a suspension. The result is a ferrous complex which, when exposed to oxygen, leads to the darkening of the ink. Other ingredients can be added such as gum Arabic which acts as a binder and prevents the particles from settling, as well as colourants that make the ink more visible while writing. Iron gall ink is very pale when applied and it grows darker as it reacts with oxygen.

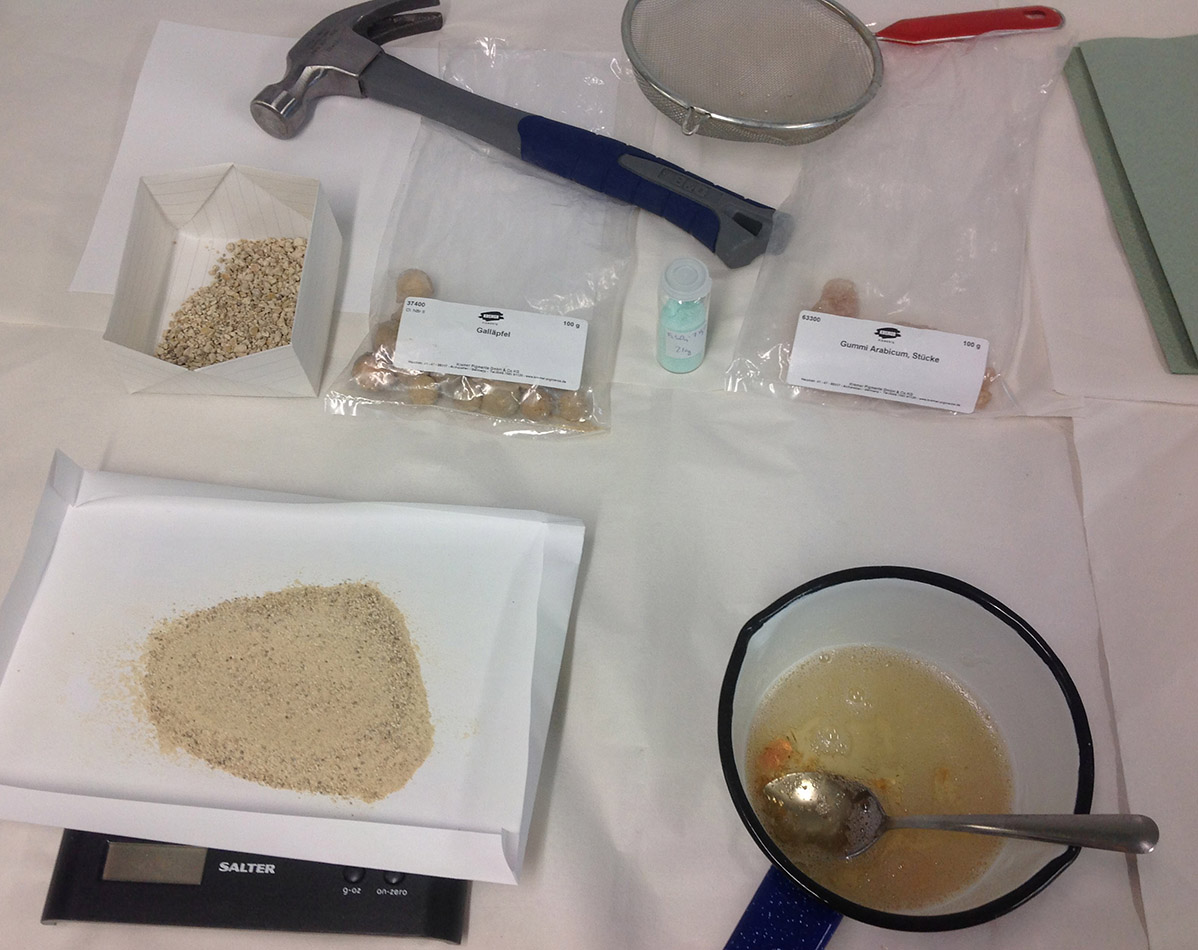

For the making of iron gall ink we have resorted to a recipe for “instant ink” mentioned in the Iron Gall Ink website, from a 1571 English book, entitled “A book containing divers sorts of hands”. This website also contains resources pointing to ingredients and where to find them.

After some help from Maia Sheridan (manuscripts archivist) to clarify the instructions, we were able to identify all the ingredients and equipment needed. The “instant ink” instructions call for white wine, gum Arabic, Aleppo galls and iron sulphate. Gum Arabic and galls were sourced from a pigment supplier and the iron sulphate was kindly provided by the Chemistry department, thanks to Dr Petr Kilian.

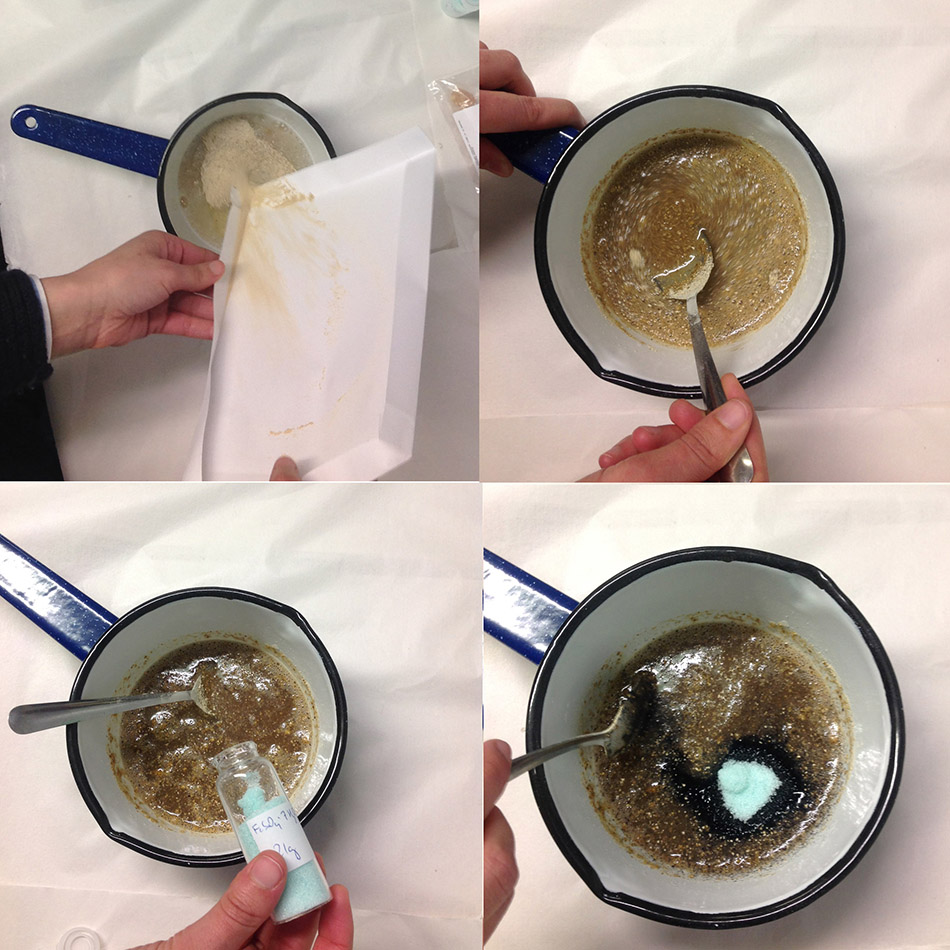

The first stage involved powdering the gum Arabic and the galls, which was done by placing them in plastic bags and crushing them as finely as possible with the help of a hammer. A tea towel was used to envelop the bags and reduce the dispersion of the contents. The gum Arabic was added to the white wine and stirred until it dissolved.

About an hour and a half later we neared the completion of the ink. The crushed galls were added into the liquid followed by the iron sulphate. As soon as the iron sulphate touched the solution the colour started turning black. A little more stirring made it into an evenly black fluid. The liquid was then sieved to remove the larger particles and is now ready for use.

In next week’s post we will be using this home made ink while we try our hand at calligraphy. Make sure to tune in then to see the results!

– Ines Fonesca

I'm not a paper expert, but isn't the twelfth century a little early for paper in Europe?

[…] so far as to follow Browne’s instructions for cutting our own quills, we did make use of the iron gall ink and handmade paper that featured in the last two weeks’ posts. For the most part, the iron […]