A conundrum solved, collectively: a 15th century Italian manuscript identified

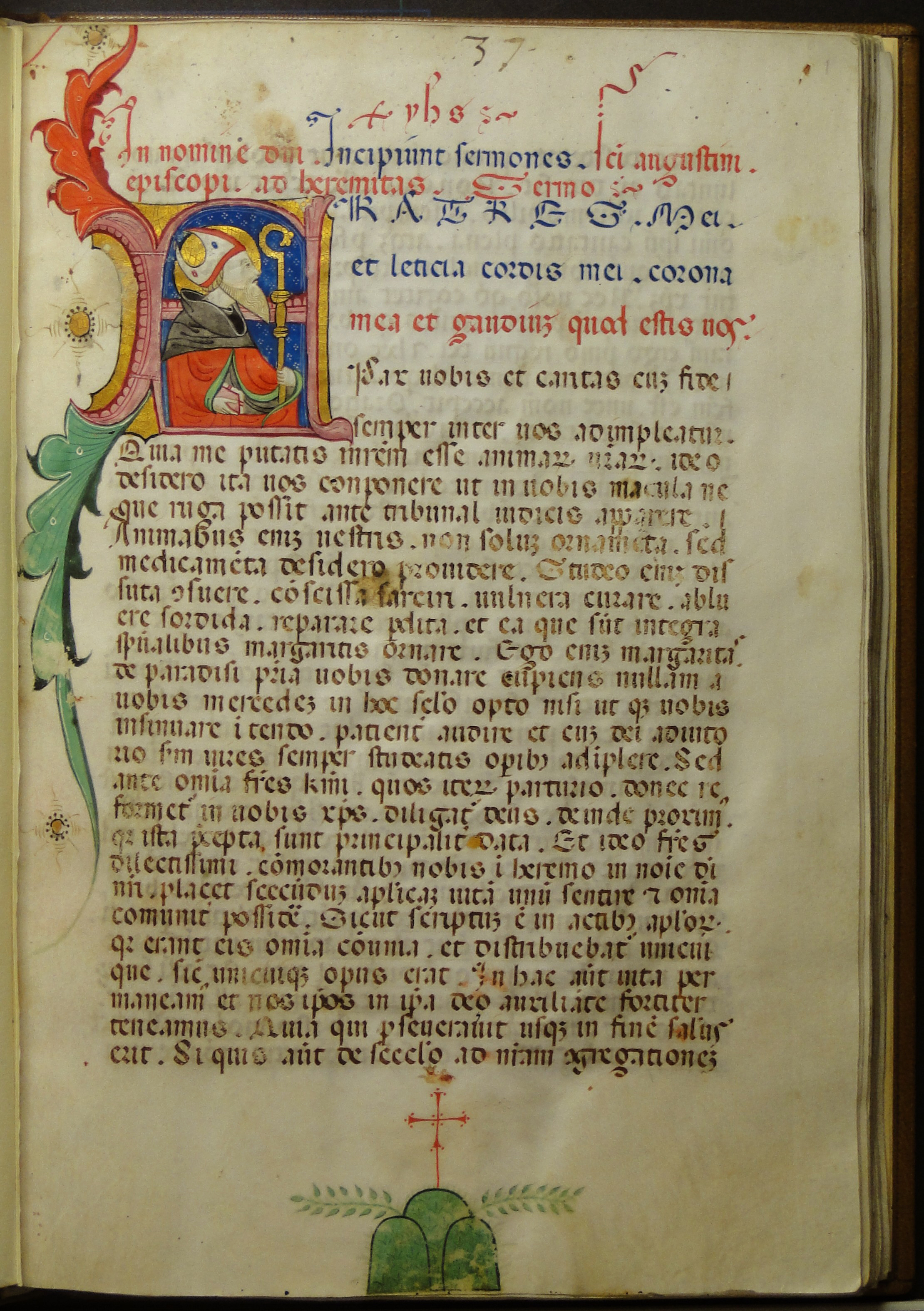

In January 2012, we posted a plea for help in identifying a motif found in one of our medieval manuscripts: msBR65.A9S2 – a Pseudo-Augustinian Sermones ad fratres eremo. This manuscript had been catalogued, and thought of for quite some time, as a 14th century Italian manuscript; this was largely based on Neil Ker & A.J. Piper’s description in their Medieval manuscripts in British libraries. v. 4, Paisley – York (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992, p. 243).

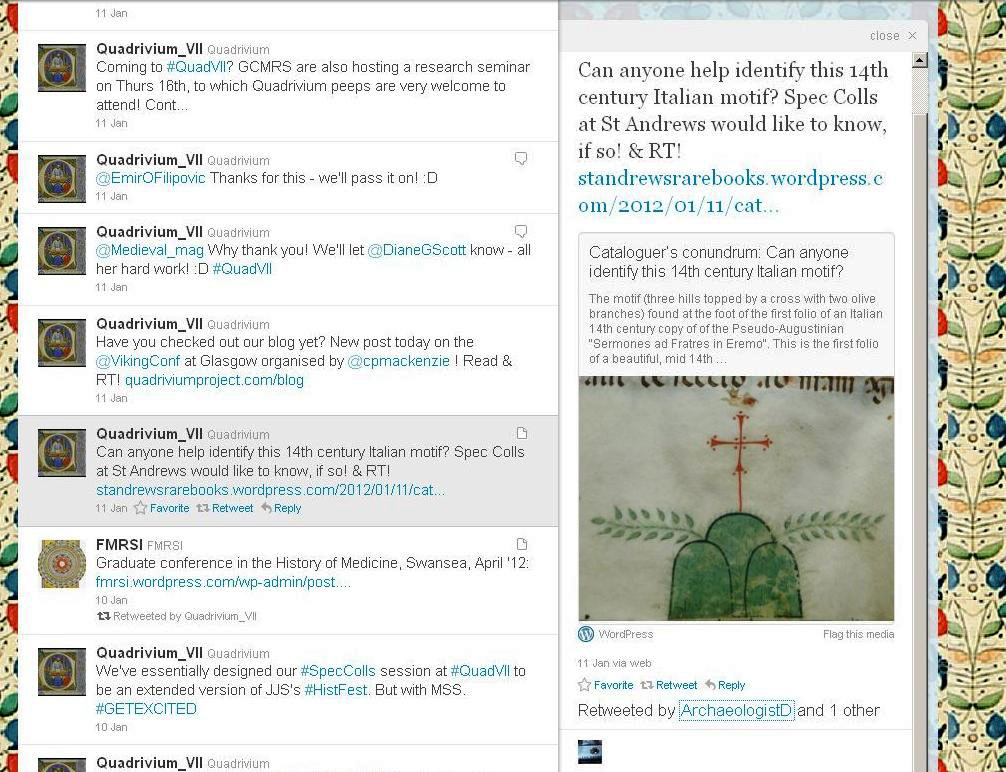

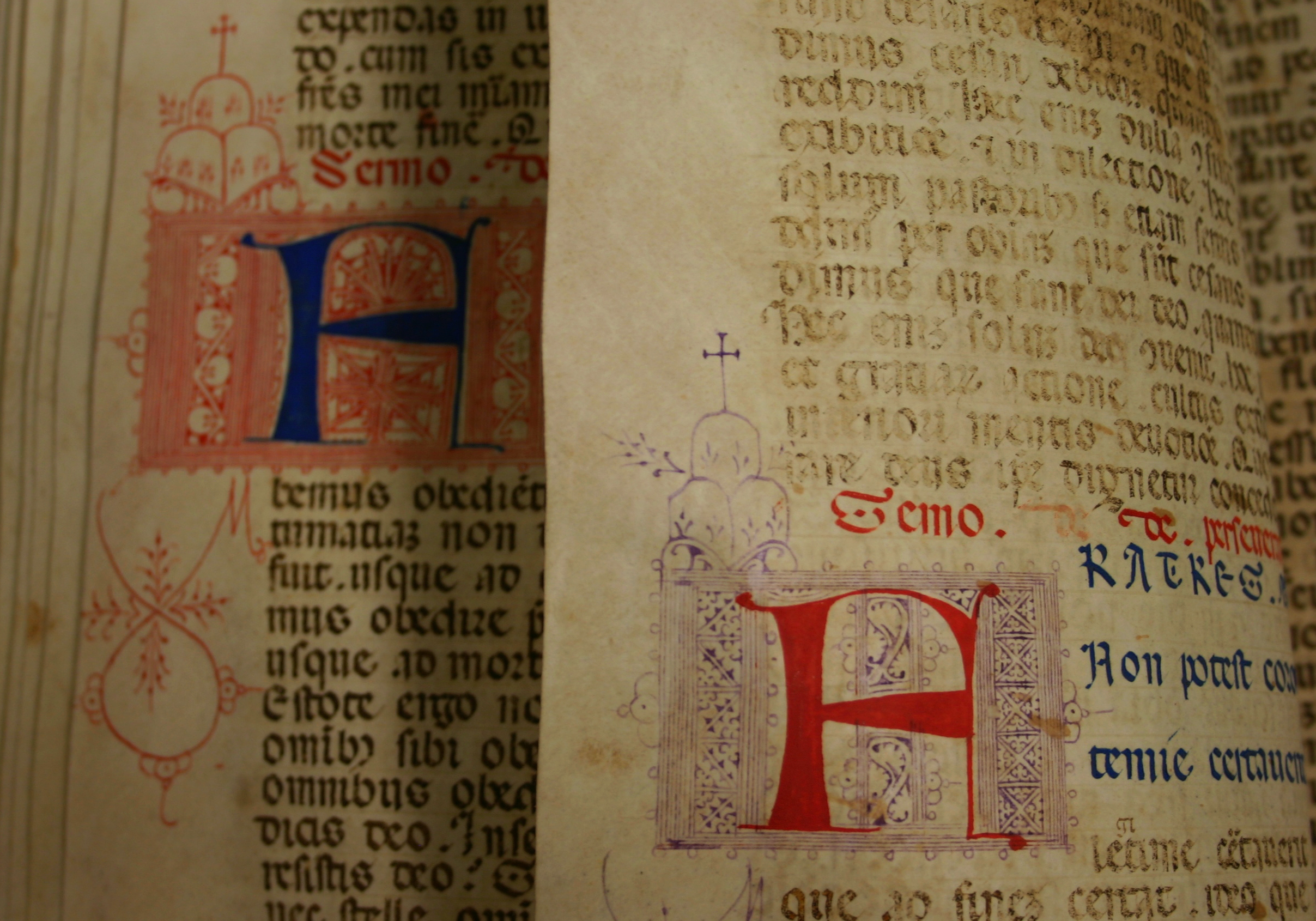

The original blog post was circulated through our usual Twitter and Facebook feeds, as well as cross-posted to some relevant list-servs, and quickly picked up interest. Within a few hours we had been re-Tweeted several times and the e-mails began pouring in. The motif at the foot of the manuscript, and found throughout in the pen-flourished initials (see image below), was quickly confirmed as the arms of the Olivetan order. What followed was a largely profitable discussion conducted through e-mails, blog comments and Twitter enquiries which resulted in us finding out much more about this manuscript than what we had initially set out to do.

As soon as the blog post had gone up we began receiving descriptions of the Olivetan symbol and general confirmations that this was, indeed, an Olivetan work. It was also suggested that the manuscript was produced either in Monte Oliveto Maggiore (because of the prominent use of the Olivetan symbol) or further south in Lecce (based on Ker’s transcription of a faint inscription on leaf 47v). However, I received an e-mail on the 11th from Professor Robert Gibbs at the University of Glasgow who identified the manuscript as 15th century, not 14th, and produced in Lombardy. This was quite interesting, as a northern attribution had not been suggested by any source before for this manuscript. This was followed, on the same day, by an e-mail sent by Professor Jonathan Alexander who confirmed that: “The illumination you send of St Augustine is attributable in my opinion to the “Master of the Vitae Imperatorum” a well-known illuminator working in Milan in the second quarter of the 15th century,” he further stated that this manuscript probably made it to sale because “French troops in Italy in the 1790’s looted the libraries in Lombardy.” Both professors mentioned the work of Anna Melograni and Milvia Bolatti as the right people to contact for further information on who might be responsible for this manuscript and when it was produced.

A high-resolution, full facsimile of the Pseudo-Augustinian Sermones ad fratres in eremo (msBR65.A9S2) is available below

[gigya embed src=”http://static.issuu.com/webembed/viewers/style1/v2/IssuuReader.swf” type=”application/x-shockwave-flash” allowfullscreen=”true” menu=”false” wmode=”transparent” style=”width:420px;height:263px” flashvars=”mode=mini&shareMenuEnabled=false&backgroundColor=%23222222&documentId=120312122724-8222ccfbb4d74816ab31e5a8135039eb”]

Anna Melograni was the first to respond in an e-mail dated 13 January 2012, in which she confirmed that: “the manuscript was illuminated in Lombardy, the date is c. 1455-1465, but the illuminator is a “follower” (seguace in Italian) of the Magister Vitae Imperatorum, but is not him.” The plot had thickened considerably: within a few days we had re-dated the manuscript 100 years later, found out that it was probably made in Lombardy, had come to us via the French invasions of the late 18th century. After circulating this new information, Prof Robert Gibbs suggested that we look at Milvia Bollati’s The Olivetan Gradual: its place in 15th century Lombardic manuscript illumination. After obtaining a copy of this work, and comparing the illuminations, illustrations and hands we knew we were getting close. On the 23rd of January we received this response from Professor Bollati: “The master of the frontispiece is from Lombard. Probably, he is to be identified with the Maestro dei fondi giallini, an illuminator who was active in the XV century (1450-1480 ca) and was trained in the Master of the Vitae Imperatorum workshop (see the entry: Maestro dei fondi giallini, in Dizionario biografico dei miniatori italiani IX-XVI, Milan 2004, pp. 461-463).”

The entry for the Maestro dei fondi giallini reads thusly (in translation):

“Active in Cremona 1450-82 for the convent of Sant’Agostino … was a protagonist, albeit in a more archaic position, of a phase of progressive influx of renaissance innovations into the still flourishing school of the late-gothic phase of Lombard illumination … [he] was influenced by/a pupil of the Maestro delle Vitae Imperatorum (sub voce) from which he adopted the frieze with leaves framing the pages and the typology of the adorned initial. He was also influenced by the Maestro Olivetano (s.v.) and Belbello di Pavia (s.v.) from which he drew the lively colour scheme and the careful drawing rhythms, within simpler and more essential compositions. His figures are weak and with a pathetic intonation, with soft and transparent skin, wrapped in wide and bright layers of colour, neatly framed by lines … his portraits have oval faces within elliptical haloes, hollow cheeks and high cheekbones, small hollow eyes with a penetrating gaze, thin and slightly hooked noses, and the corners of the mouth facing downwards … ascribed to the ‘Maestro’ the frontispiece of a Summa de casibusconscientiae by Bartolomeo di San Concordio, signed in 1482 by a brother Andrea from Pavia and belonged to the library of the Augustinian convent of the Incoronata in Milan (Ambrosiana etc.). In the initial is portrayed St Augustine writing with a nun, identified as Saint Monica. This should be his last known work: the lines characterizing his earlier works and defining the draping and the position of the figures with sharp or right angles are now more fluid, softening figures and gestures.”

We have learned a great deal about this one manuscript in the month following our initial post, mostly through various social network mediums. What began as an experiment in a new way of tapping into new scholarly networks ended up telling us more about this manuscript than we have ever known. We are very thankful to all that looked at the blog post (over 800 hits!) and responded to us via Twitter, Facebook, e-mail and post. We hope that the enclosed facsimile and this synthesis is a little reward to you all!

–DG

Isn't wonderful how something like this could explode into all this wonderful answers. You put it on line and it sparks all kinds of interest. I found the history of the manuscript as interesting as all the emails of people filling in the blanks of missing info. http://www.pierotucci.com/clothing/new_collection/

This is an amazing story! It's so inspiring to a young librarian-in-training to see how librarians and professors can work together to increase the world's understanding of one (very beautiful) manuscript!

[...] a full update on this conundrum, see this post from 12 March 2012.*** The motif (three hills topped by a cross with two olive branches) found at the foot of the [...]

[...] A conundrum solved, collectively: a 15th century Italian manuscript identified [...]

[...] Rare book blogs range in level of commentary: from the very deep, scholarly works to the casual, “hey, look what I found today” style. All of these work, as long as you are writing original content and are open to having a discussion on-line and out-in-the-open about what you’ve written about. Terry Belanger, in a recent promotional video for the Rare Book School, said that “Most collectors want to talk about their collections, most friends of collectors don’t want to listen,” but I think that if we, as professionals, talk about what excites us about these thing in the open, on the web, more people will find out about these things, and more people will listen. Scholarly and trade conversations have been locked up in print publications and don’t serve the new generation of potential users of rare books or certainly the casual web surfer who stumbles upon an image of a great rare book. Previous correspondence between sellers, collectors, librarians and researchers are full of information about where copies of a certain book were and in what state. Having a conversation, out in the open, where it can be read and seen by all is key. We shouldn’t be afraid to say that we don’t know something or even to get something wrong. Confronting a known community with a question which stokes their minds will ultimately produce results. [...]

[...] Rare book blogs range in level of commentary: from the very deep, scholarly works to the casual, “hey, look what I found today” style. All of these work, as long as you are writing original content and are open to having a discussion on-line and out-in-the-open about what you’ve written about. Terry Belanger, in a recent promotional video for the Rare Book School, said that “Most collectors want to talk about their collections, most friends of collectors don’t want to listen,” but I think that if we, as professionals, talk about what excites us about these thing in the open, on the web, more people will find out about these things, and more people will listen. Scholarly and trade conversations have been locked up in print publications and don’t serve the new generation of potential users of rare books or certainly the casual web surfer who stumbles upon an image of a great rare book. Previous correspondence between sellers, collectors, librarians and researchers are full of information about where copies of a certain book were and in what state. Having a conversation, out in the open, where it can be read and seen by all is key. We shouldn’t be afraid to say that we don’t know something or even to get something wrong. Confronting a known community with a question which stokes their minds will ultimately produce results. [...]

[...] allen Unterstützer/innen mit einer Zusammenfassung der Ergebnisse und einem Faksimile unter <http://standrewsrarebooks.wordpress.com/2012/03/12/a-conundrum-solved-collectively-a-15th-century-it...> Geschrieben von Joachim Räth. Veröffentlicht am Donnerstag, 15. März 2012 um 20:00. [...]

[...] Kollaboratives Arbeiten, z.B. zur Identifizierung eines alten Manuskripts[3] [...]

[…] Auf diese Weise wurden über Blogs übrigens bereits gemeinsam Handschriften identifiziert: A conundrum solved, collectively: a 15th century Italian manuscript identified, in: Weblog Echoes from the Vault. A blog from the Special Collections of the University of St Andrews, 15.3.2012, http://standrewsrarebooks.wordpress.com/2012/03/12/a-conundrum-solved-collectively-a-15th-century-it… […]