Special Collections Visiting Scholars – Friending Cicero

The moment you login to Facebook you are faced with an up-to-the-second archive of vacation photographs, pet videos, political screes, and daily frustrations of your close friends, and distant acquaintances. Yet social networks like Facebook are simply the most recent repositories of friendship. At least since Petrarch’s 1345 discovery of Cicero’s personal letters to Atticus in a cathedral library in Verona, libraries have been a primary destination for those seeking materials – notably books, deeds, and wills – that document relationships and shared property between friends, both real and imagined. For Petrarch, his discovery of Cicero’s letters was the discovery of a long lost pen pal.

St. Andrews University Library is one such important archive of friendship that drew me to its collections through their Visiting Scholar Scheme. I am grateful to be the recipient of this scholarship because I am currently working on a book called “Words with Friends: A Prehistory of Digital Textuality” that benefits greatly from their impressive collection of Ciceronian manuscripts and books. My larger project seeks to demonstrate the ways that premodern conceptions of friendship are reemerging within the networked environments that have come to define 21st century Internet culture across the globe, but my visit to St Andrews was focused on one section of the book, “Salutation,” which addresses the prehistory of social networking, notably the Twitter and Facebook message, whose instantaneous and abbreviated character has transformed written correspondence. In an effort to trace the origins of this digital communication, I have been examining the medieval art of writing letters, known as ars dictaminis or dictamen, which established the rhetorical principles (i.e. salutation, securing of good will, narration, petition, conclusion) for most western epistolary genres, from the memorandum to the e-mail to the text message. Dictamen is often characterized as impersonal, formulaic, and public, far from the intimate, sincere, and private letters of the modern era. Scholars generally agree that the prescriptive teaching of medieval dictatores was gradually superseded in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries by the work of early humanists, such as Petrarch, who preferred the less hierarchical expressions of friendship represented by the treatise De Amicitia and personal correspondence of Cicero.

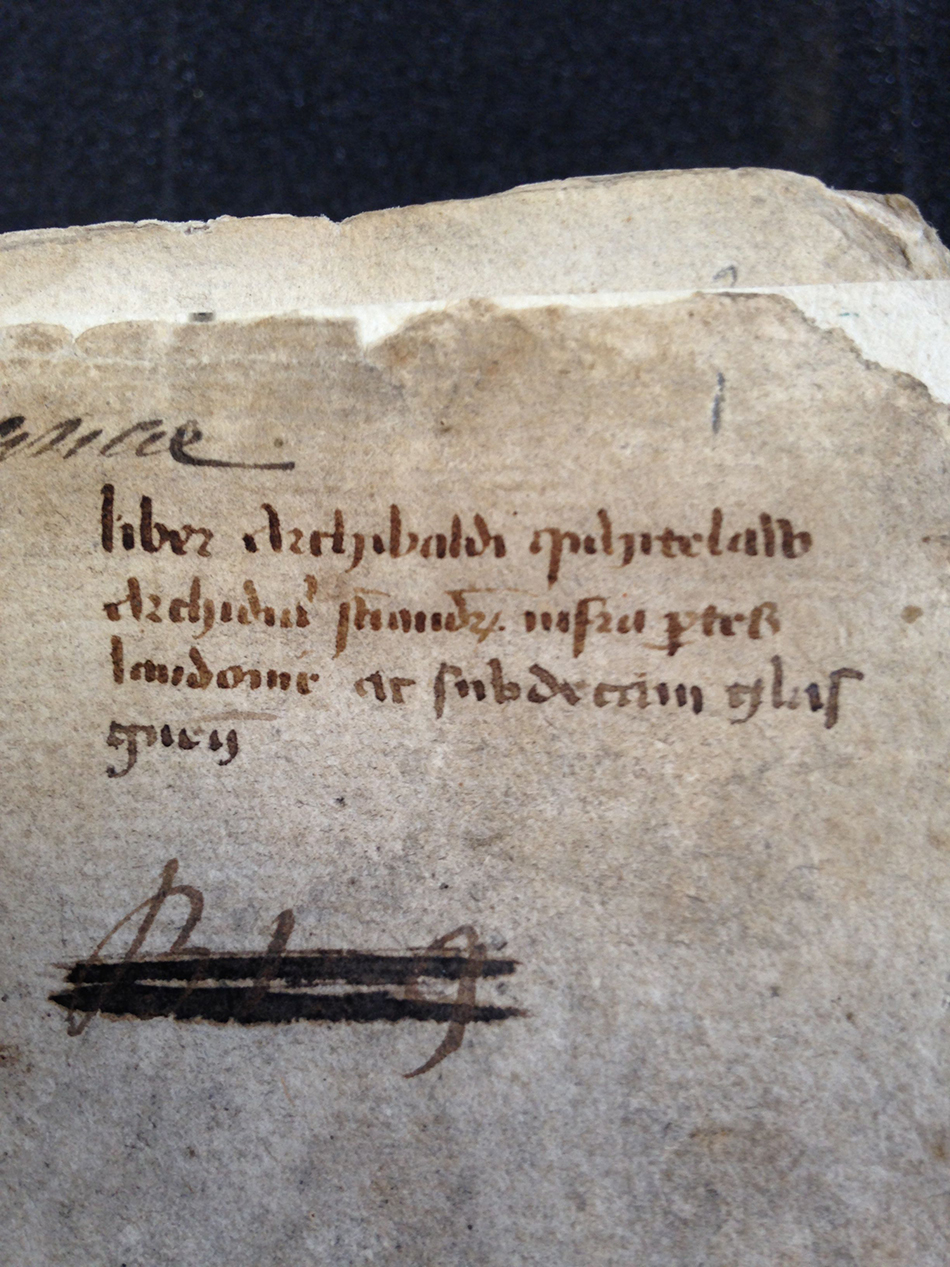

Interestingly, the obsolescence of dictamen in Britain was accompanied by the importation of Cicero’s works printed on the continent. An important figure in this development was Scotland’s Archibald Whitelaw, royal secretary and tutor to James III, who studied and taught at St Andrews, all the while amassing an archive of classical works. Considered to be one of the earliest Scottish humanists, Whitelaw possessed a library of printed books, including four from Venice, which specialized in all things Ciceronian. Cicero was so beloved among Venetians that their first printer Giovanni da Spira selected Cicero’s Ad Familiares (“Letters to His Friends”) as the first (and second) book he would print in Venice. He was even granted a printing monopoly in 1469 to discourage the anticipated competition.

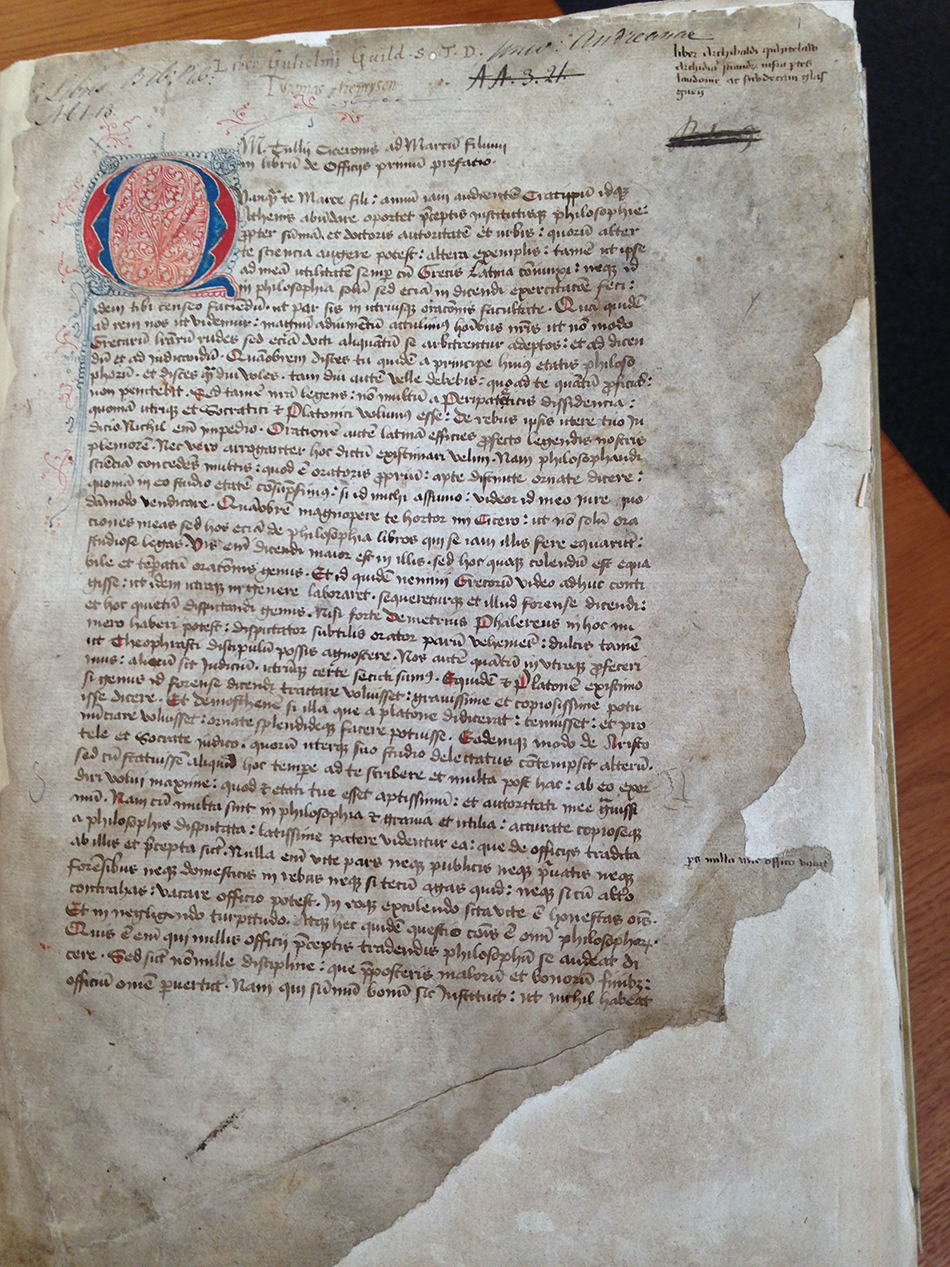

Whitelaw appears to have been grappling with continental Ciceronianism when he encountered the 1471 Roman edition of Cicero’s Opera Philosophica. St Andrews University Library MS PA6295.A2A00 is a manuscript copy (ca. 1480) of this printed book, written in a script that attempts to imitate a humanist hand. While this palaeographic feature is worthy of investigation in itself, my focus was on Whitelaw’s marginalia, which is signed and distinguishable throughout the manuscript. As the length and number of his comments indicate, Whitelaw was clearly engaged with Cicero’s De Amicitia (“On Friendship”), but his greatest dedication was to Cicero’s De Officiis (“On Duties”), a vastly influential work of moral and political philosophy.

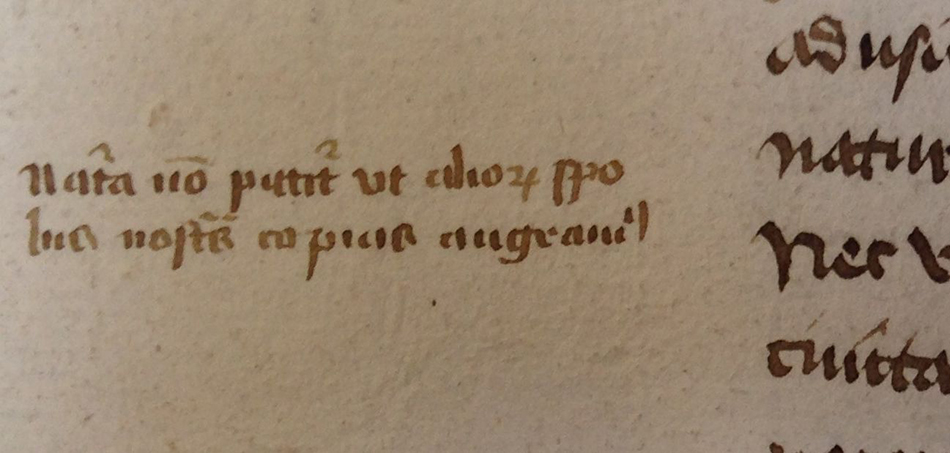

Whitelaw’s investment in De Officiis interested me for two reasons. First, it was considered by Petrarch and later humanists to be an intimate letter of advice from father to son. Whitelaw’s interest may reflect his engagement with this ‘new’ epistolary style, a kind of political rhetoric of friendship. Second, De Amicitia and De Officiis share a common concern with the role of utility (or advantage) in human affairs. In De Amicitia (XIV.51) the relationship is one of the chicken and the egg: “Friendship is not the result of advantage, but advantage of friendship” [“Non . . . utilitatem amicitia, sed utilitas amicitiam secuta est”]. Whitelaw appears to have this dictum in mind when he approaches Book III of De Officiis, the most heavily glossed book in the manuscript. To highlight a similar point Cicero makes about using others for personal advantage (III.5), Whitelaw adds the summative gloss: “Nature does not permit that we increase our power with the spoils of others” [“Natura non patitur ut aliorum spoliis nostra copias augeamus”] . This comment highlights his unassuming dedication to friends, especially when we consider his legacy as “the survivor of more political crises than any other royal servant,” a man who endured the tumult of the reign and eventual overthrow of his tutee James III.

Without Whitelaw’s marginalia, we would have limited access to his thoughts on friendship, which could only be inferred from the surviving contents of his library, historical records, and his address to King Richard III. His glosses therefore comprise a network of commentary on friendship that would be archived and later extended by the book’s future owners, swapping words with imagined friends, much in the style of Cicero and Petrarch. Social networks such as Twitter and Facebook may happen in ‘real time,’ but they are based on this premodern logic of archival friendship, with the number of comments and “likes” indicating the level of collaborative investment of one’s ‘friends.’ While such expressions of friendship are often empty gestures devoid of any sincere feeling of affection, these rhetorical acts often express a real desire for intimacy, even in the absence of sympathetic recipient. Most importantly, these epistolary friendships have a public material life within these spaces, wherein objects of intimacy can be recorded, archived, searched, and even recovered.

Alex Mueller

University of Massachusetts, Boston