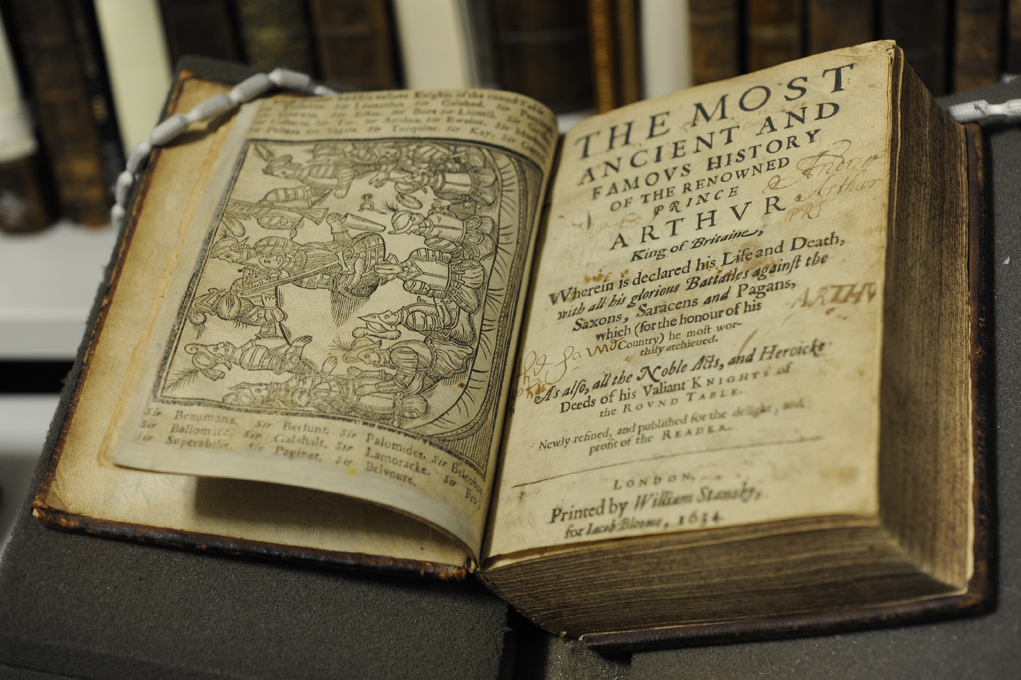

New acquisitions spotlight: Malory’s History of King Arthur (1634)

The Most Ancient and Famous History of the Renowned Prince Arthur King of Britaine was the last seventeenth-century edition of Thomas Malory’s great medieval prose romance, the Morte Darthur. After it, no new edition was printed until the early nineteenth century. This, therefore, was the Malory of Milton, of the romantic poets and of Walter Scott, who recorded owning a copy as a boy.

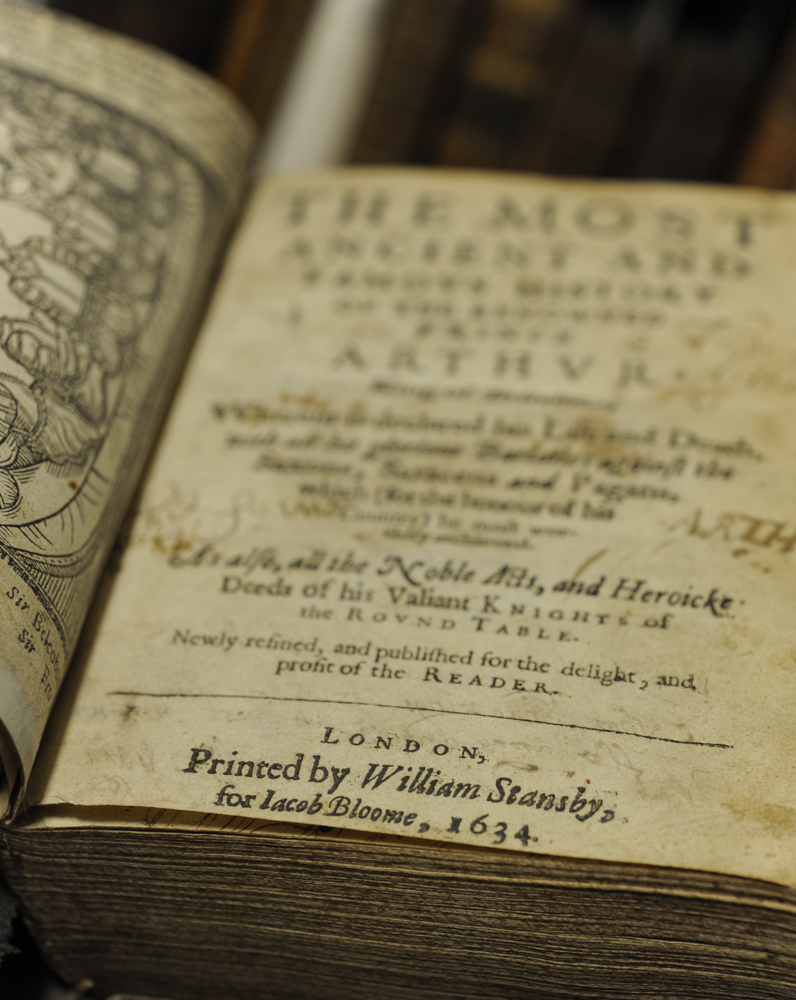

The volume was printed by William Stansby for the stationer Jacob Blome in 1634. It represents a break with previous early modern editions, all of which descended from William Caxton’s 1485 Malory. The Blome-Stansby Famous History is a compact book seemingly addressed to a more popular market than the expensive folios that preceded it. It introduces a new preface addressed ‘to the Reader, for the better illustration and vnderstanding of his famous historie’, and it adds in a woodcut illustration of Arthur and his knights at the start of the text. This became notorious for the way it literalised the king’s centrality to his famous round table. In 1663 Samuel Butler’s mock-heroic poem Hudibras joked that

“Arthur wore in Hall

Round-Table like a Farthingal”

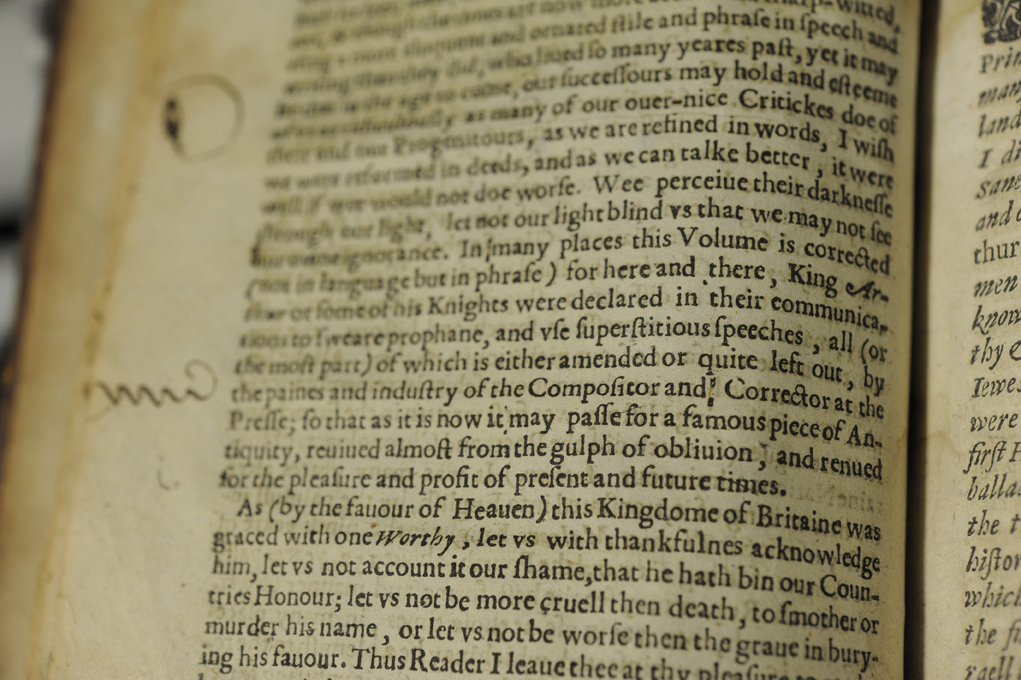

The preface explains that the romance has been expurgated to bring it in line with seventeenth-century tastes:

“In many places this volume is corrected (not in language but in phrase), for here and there king Arthur or some of his knights were declared in their communication to swear prophane, and use superstitious speeches, all, or the most part, of which is quite left out, by the pains and industry of the compositor and corrector at the presse, so that as it is now it may passe for a famous piece of antiquity, revived almost from the gulph of oblivion.”

The modernisation of some spellings in the Stansby edition was another reason for the book’s long-term appeal. Around 1807 Sir Walter Scott considered producing his own popular edition of Malory. ‘I don’t want to make it an antiquary’s book’, Scott wrote to the bibliophile Richard Heber, ‘and shall therefore print from Stansby’s edition in 1636 [sic] I think, because the language is perfectly intelligible’. In the end Scott abandoned his plan, but the Stansby edition lived on well into the nineteenth century in a number of new incarnations. It was the basis for two popular editions in 1816 and for the antiquarian Thomas Wright’s edition of 1858 (like Scott, Wright settled on the Stansby text as it was the ‘most readable’). These editions often applied further expurgations to the already ‘corrected’ text: one of the 1816 editions, edited by Joseph Haslewood, remarked that ‘some sentences needed highly pruning, to render the text fit for the eye of youth; and that it might no longer be secreted from the fair sex’.

The preface to the Stansby edition addresses a more general ‘reader’, but a particular feature of the new St Andrews copy is a handwritten inscription indicating that it was once owned by ‘Elizabeth Purcell of Kirton in the year 1699 afor she was Married’. On the basis of this evidence, it would seem that seventeenth-century women readers enjoyed relatively open access to Malory’s Arthuriad in comparison to their eighteenth-century and Romantic counterparts.

More about this acquisition can be read in this release issued by the University of St Andrews Press Office.

Teaching Fellow in English Literature, School of English

-&-

Lecturer, School of English

Reblogged this on First Night History.