Where we find new old books, chapter 5, part II: A beginners’ guide to uncovering rare book treasures: the journey of a 500 year old book

Here, our Lighting the Past team complete the story of their recent adventures uncovering the story of one of our new finds.

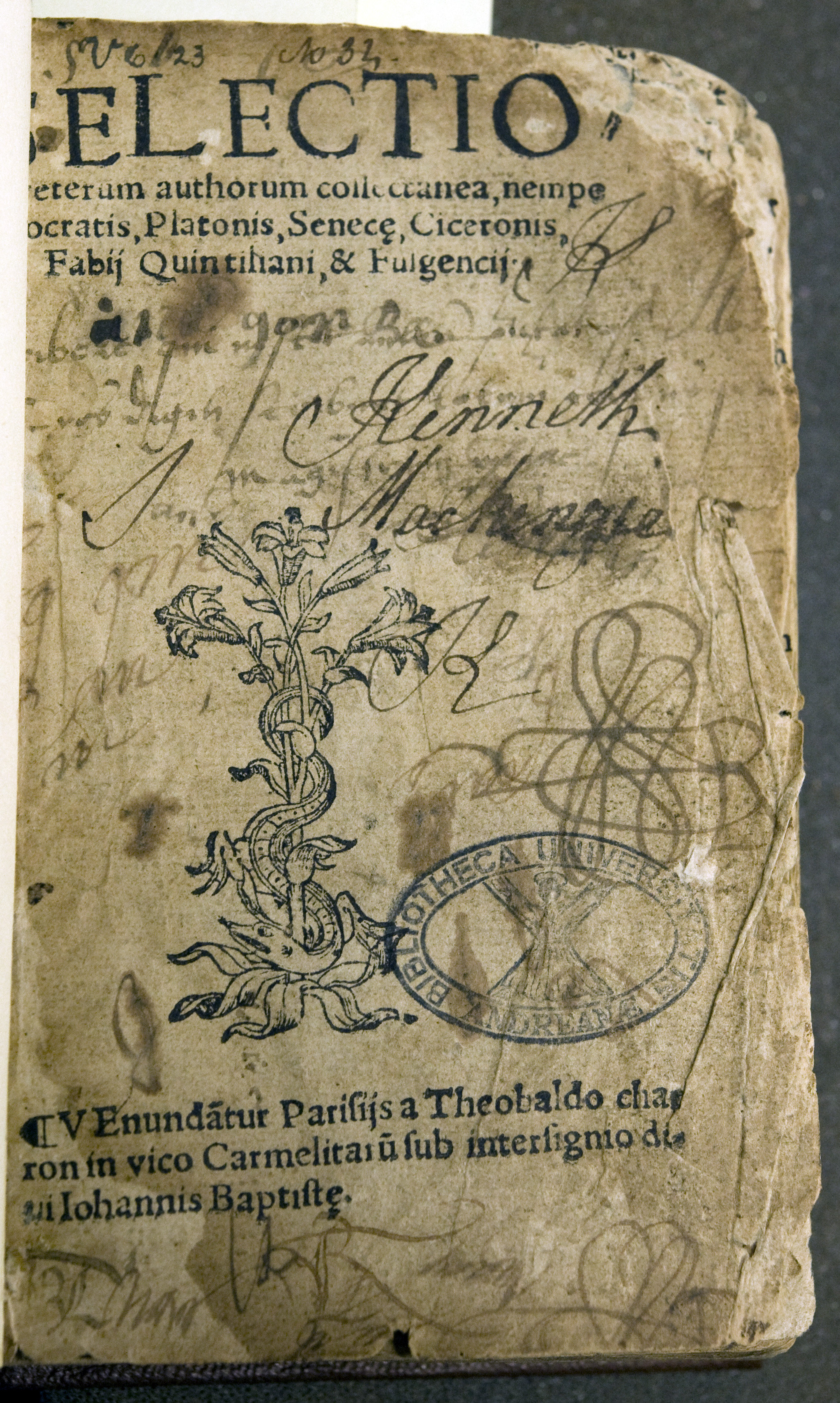

Provenance of a 16th century Parisian sammelband

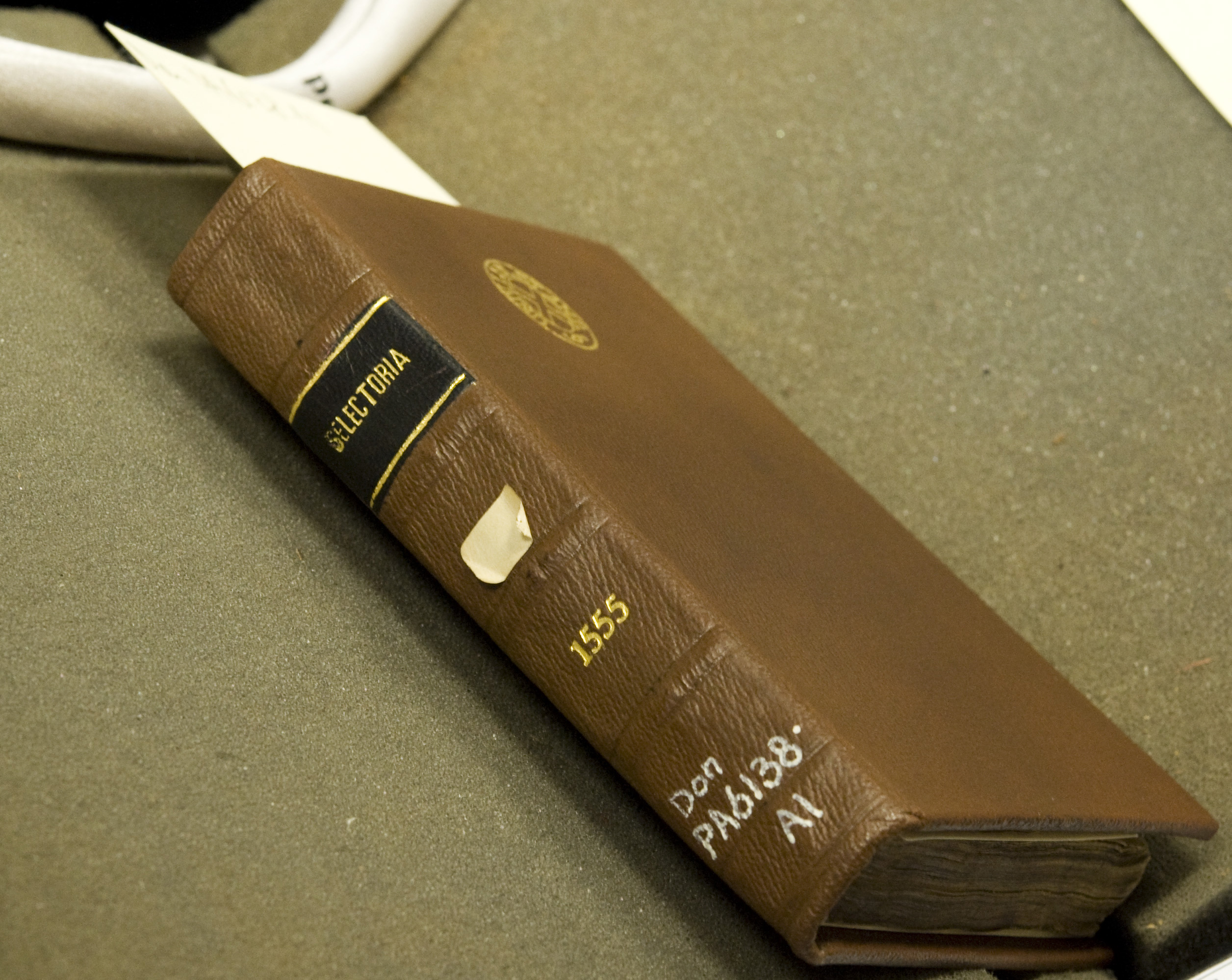

At some point during the sixteenth century, our wee volume [Selectoria Don PA6138.A1] made its way to the British Isles. The nascent printing industry was not established in Scotland until the second half of the sixteenth century; as a result, book dealers provided much-needed access to educational texts. This particular compilation of school texts attests to the wide influence of Desiderius Erasmus, famous Renaissance Humanist. While in Italy, Erasmus himself served as the boyhood tutor of King James IV’s illegitimate son, Alexander Stewart, the teenaged Archbishop of St Andrews. Stewart was also the co-founder of St Leonard’s College in 1512.

Traditional cultural and political connections between Scotland and France can also help to explain the circumstances surrounding this journey. Around the time our book came to Scotland, the Humanist Bishop Robert Reid was involved in establishing the first lectureships, in Greek and Canon Law, in Edinburgh under the patronage of the French Queen consort, Mary de Guise. This “Tounis College” (Town’s College) officially rebranded in 1583 as the University of Edinburgh.

Evidence

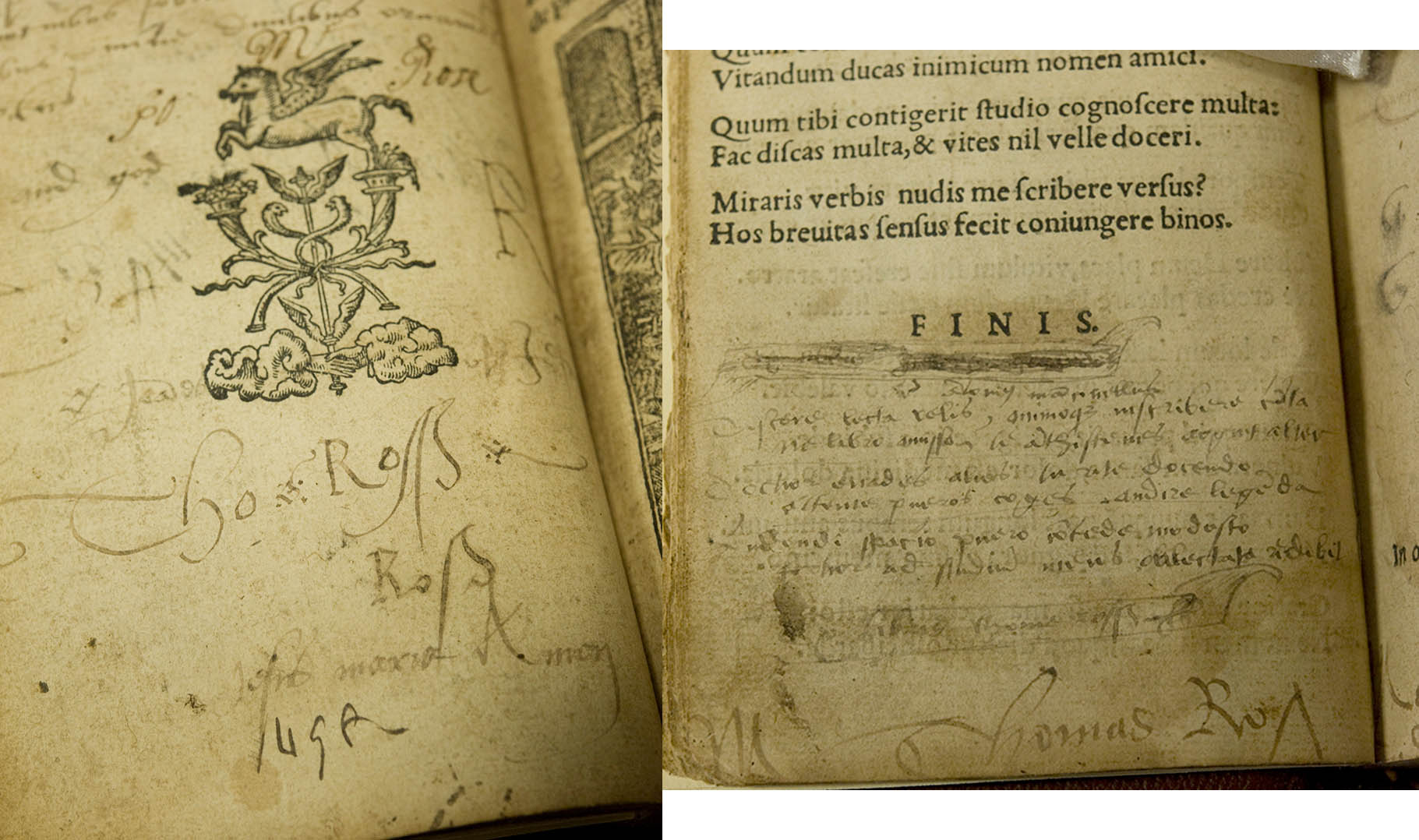

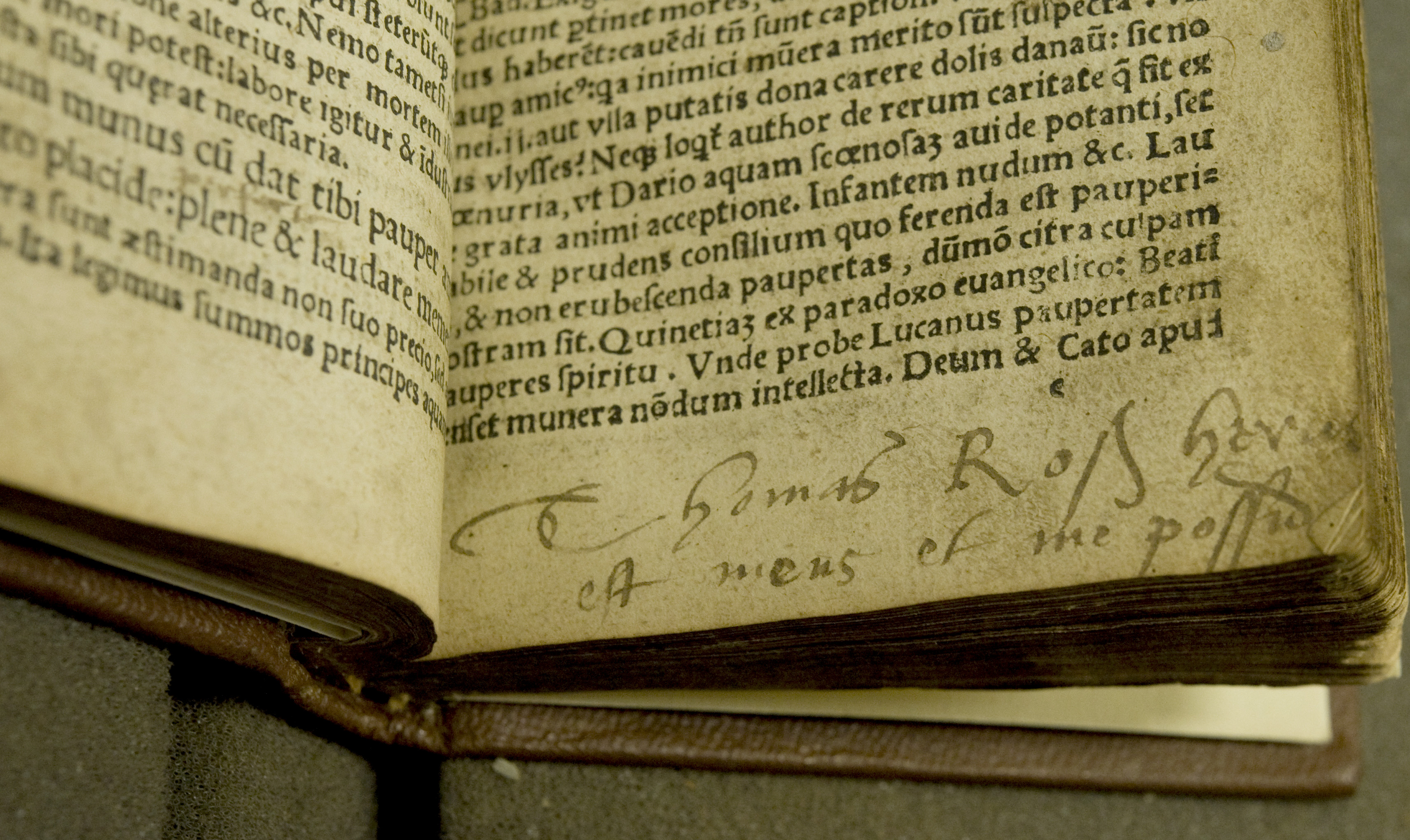

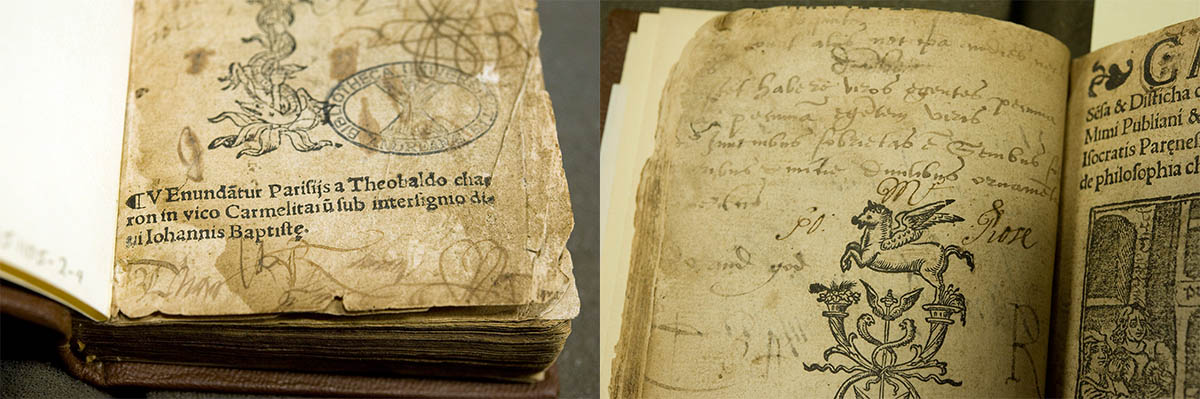

The volume’s most visible owner from this early period is one Thomas Ross, whose name or initials occur on no fewer than six separate pages:

The book may have been passed down in the Ross family, for the name George Ross also occurs several times throughout the volume, though in a later hand:

![George [P?] [R] Ross](https://special-collections.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/files/2016/01/pic-4.jpg?w=470)

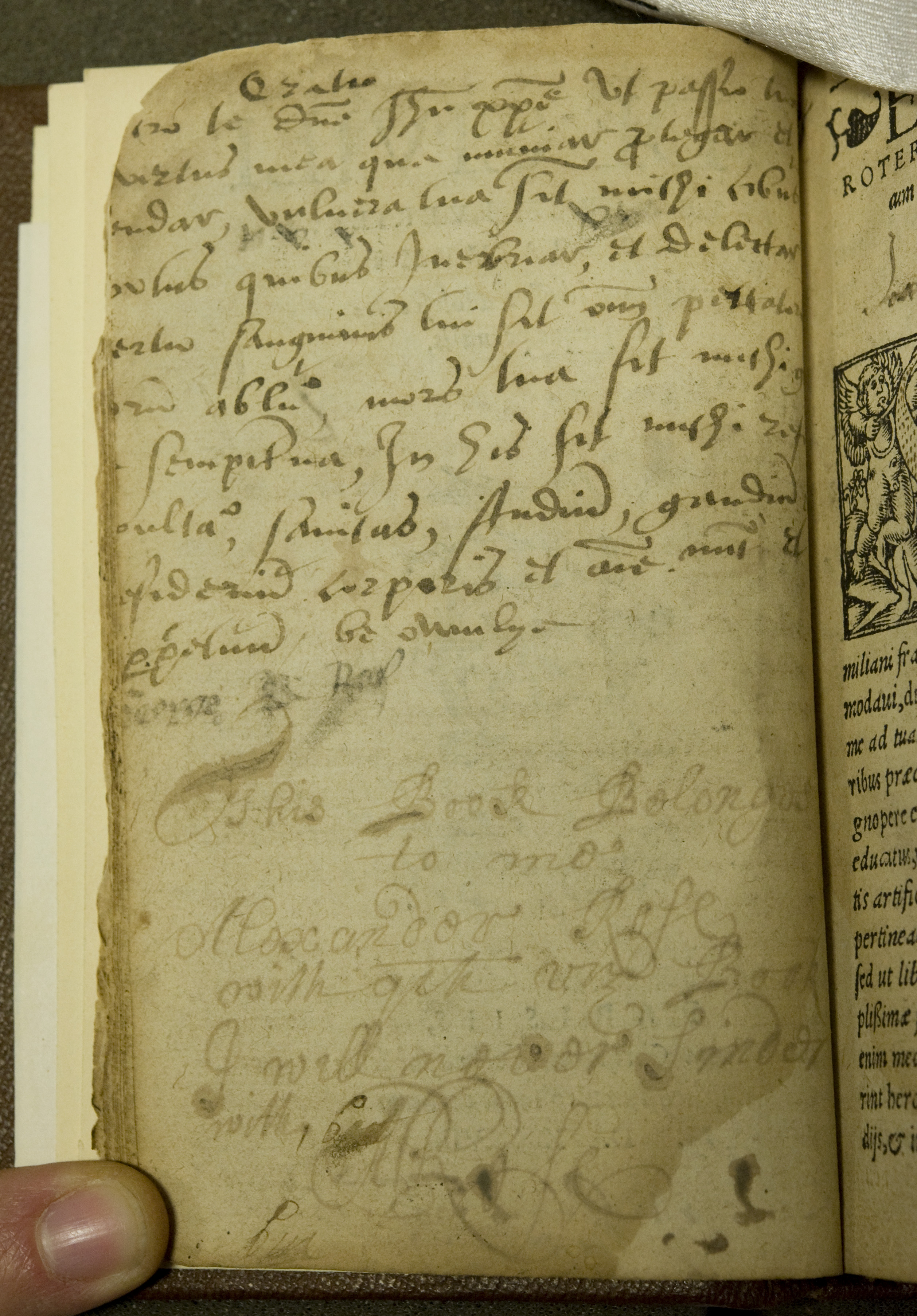

A certain Kenneth Mackenzie practiced his penmanship on the title page to the Selectio veterum authorum collectanea:

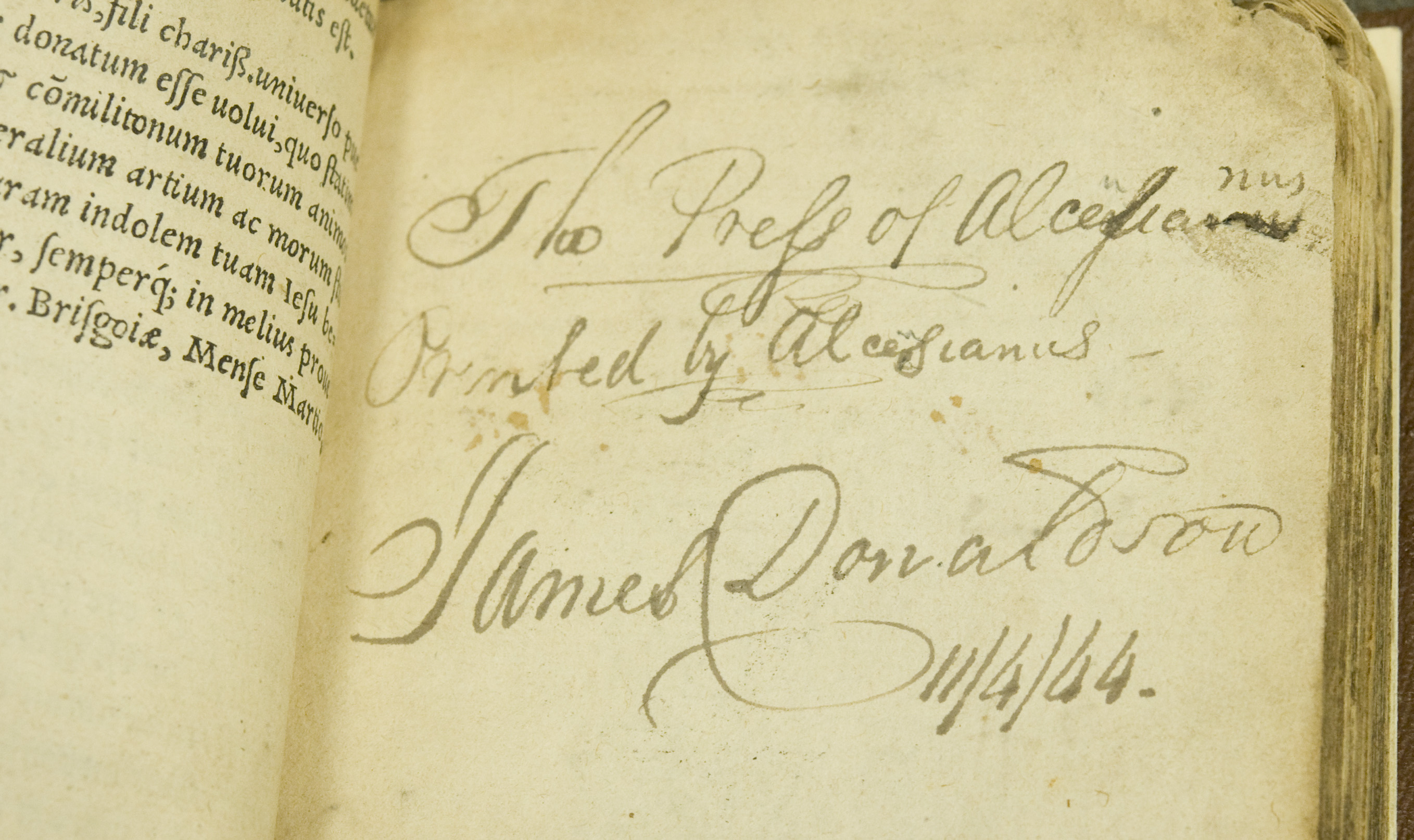

Finally, on the 11th of April, 1864, James Donaldson, perhaps inspired by such a prolific show of penmanship, added his own inscription.

Conclusion

This book contains inscriptions made by a number of people, which reinforces the importance of examining books for physical evidence of earlier ownership. At present we have no evidence linking individual people to the book and its history.

Provenance, or the history of ownership, of individual books and collections is a growing area of research. Linked to this is an increasing interest in the use of books during their lifetimes, in the cultures and practices of reading, and in the history of book-collecting. Anyone interested in the provenance of the Library’s printed collections should first consult the online catalogue, which contains provenance information for many Special Collections books. The Library’s own archives contain a great deal of information on the history of our collections including manual records of provenance such as accession registers, and sheaf catalogues. There might also be relevant information in personal papers and correspondence. We need to turn to these sources to see if there is more information about the history of this book.

–Lighting the Past team

https://certainmeasureofperfection.wordpress.com/grindleton-brierley-the-grindletonians/

[…] Source: Where we find new old books, chapter 5, part II: A beginners’ guide to uncovering rare book treasu… […]

[…] Isn’t this blog post title intriguing? “Where We Find New Old Books, Chapter 5, Part I, A Beginners’ Guide to Uncovering Rare Book Treasures: A 500-Year-Long Tale Between Parisian Pages” Read Part II here. […]

The puzzle deepens! I have read numerous late-16th/early-17th c. documents and found on many occasions the final 's' in a word was a mere squiggle. Looking at 'Alexander Rose' I notice he used the form of 'e' that I keep coming across, which to modern eyes appears back-to-front. e.g. 'belongs', 'me', 'Alexander', etc. This does not match the 'e' in 'Rose'. Of course Alexander may deliberately have changed his name as happened in the Home/Hume family with the celebrated philosopher David choosing the latter. It is also noticeable that Thomas Ross tried two versions of his signature - one using ß on its own. In the first sample was Thomas using three 's's to create a possessive?

[…] as a team, some blogs were co-authored, such as that on how to read minds, and another on a 16th-century sammelband. In April 2016 residents and visitors to St Andrews had the opportunity to see some of the items […]

[…] straight out of the Da Vinci Code, or Indiana Jones – I highly recommend you check out part 1 and part 2 of the blog post that Emily and I wrote on […]