The curator’s goodbye

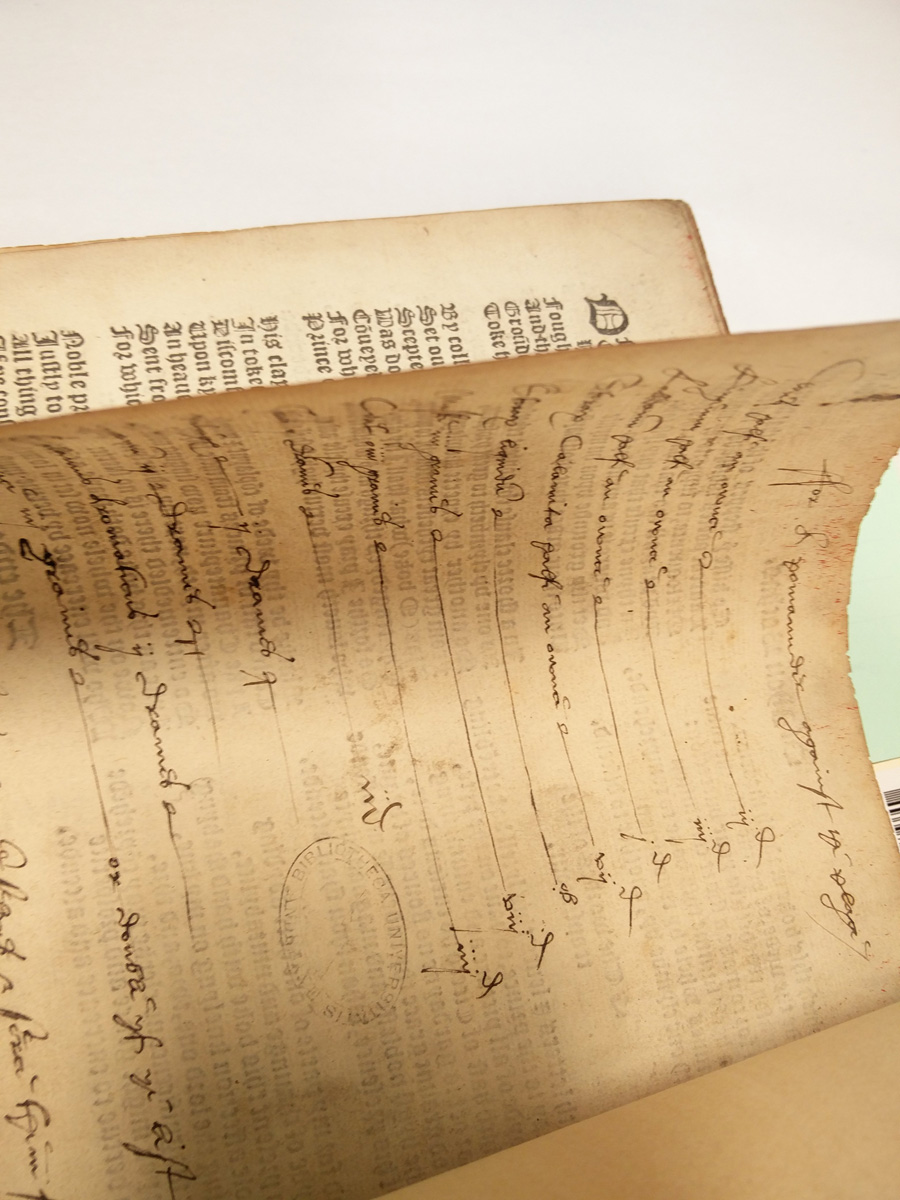

Today is my last day of work at St Andrews. After more than six years in this lovely, quiet corner of the world, I’m heading off for a new position, a new collection, and a new group of colleagues. However, over the past few weeks I’ve been chewing on what it means for a curator (or librarian, or archivist) to leave the collections they have held in their charge. What does it take to leave the books that have been your companions for more than half a decade? How do you leave behind the physical memory of “oh yes, this book on this shelf has got killer manuscript pastedowns”, or, “just down here in this range there’s at least a dozen Cockerell bindings”, or, “man, this entire collection is just waiting to be cracked open.” How do you leave it behind? How do you say goodbye to your collections?

Although I’ve worked for two other distinguished libraries, I was not in either of those roles as long as I’ve been in St Andrews, nor was I in a position anything like a curator. My previous jobs as rare materials cataloger (without the “u”, as it was in the States) and as assistant librarian put me in the same arena as the kind of work a curator does, but the time I’ve spent at St Andrews has had a healthy mix of the curatorial and the metadata creation. I’ve gotten to know the collections from the inside out [cataloguing previously uncatalogued works], and the outside in [selecting books for classes or exhibitions, and getting to know them in the process]. So, when I say that I know some of our rare books collections intimately, like old friends passing on the street, and for the rest of the collections (we’re talking 200,000+ rare books here, folks) I know their faces if not their names, then that’s where this is coming from.

Connections

As I thought more and more about what I will miss about my collections, or, more accurately, the collections that have been in my care (but really, most of us curators think of them as “my collections”) I realised that I will miss the connections that I have witnessed, been a part of, or made myself through the medium of the book. In essence, that’s really what a book is: a way for one person’s mind to connect to another person’s mind and to communicate some kind of information (be it dogma, or mathematics, or a fictional tale) over hundreds, even thousands of years. The book is a way for two minds to meet.

I have mentioned before that on my desk I have kept a quote from Walt Whitman’s poem ‘So Long!’ which has long haunted and inspired me:

“Camerado! This is no book;

Who touches this, touches a man;

(Is it night? Are we here alone?) It is I you hold, and who holds you;

I spring from the pages into your arms – decease calls me forth.”

Whitman’s envoi, found in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass, captures the magic of pulling a book off the shelf for the first time; a book slowly reveals author to reader and slowly releases its secrets. It is a private experience, shared between two imaginations.

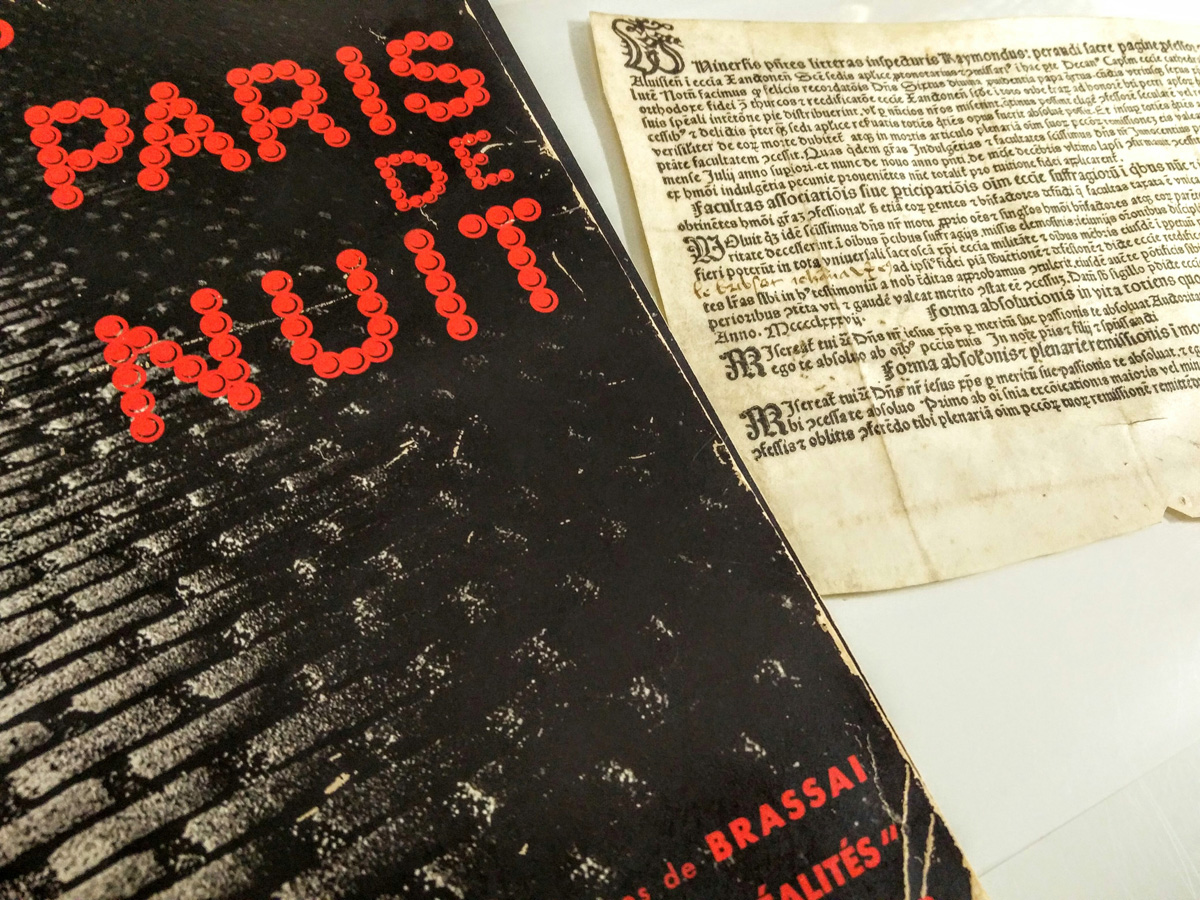

Creating connections

One of the greatest privileges that a curator has is being part of that cycle that connects reader to author, whether it’s through a research enquiry, in the reading room, or in the classroom. A curator is the physical connection between books and manuscript locked away in secure stacks and the reader/researcher in the wild. There is something wonderfully satisfying that happens when you see the right book or manuscript land in the right person’s hands, whether it’s a student’s first time turning the pages of a 15th century folio or a researcher explaining to you the importance of a first edition of a 19th century novel as they handle it for the first time. Being part of that experience has been electrifying.

Making connections

For the second time on this blog, I’m drawn to Joe Cocker’s masterful cover of The Beatles to express my emotions fully:

The most lasting impact that my work as a curator here at St Andrews will have is the relationships, the connections, which I have made due to the books in my care. When a curator starts the dialogue of a research enquiry, or fields an exhibition proposal, or develops a class with a tutor, he or she starts building a relationship. Sometimes those relationships are fleeting, an enquiry answered and the researcher moves on. However, many times the enquiry leads to another question, and possibly bringing the researcher into the stacks, into our realm, to see all the possible paths that a collection can provide. This moment, which is often a researcher’s first time having the vault doors opened for them, is what I call the “Wonka-moment” (although I’ve never perfected Wilder’s foot work). The connections made to other people through the joint wonder and appreciation of all the wonderful books and manuscripts at our fingertips is visceral, and wonderful.

This blog, too, has made so many connections possible from such a remote place. I started Echoes back in 2011 as a small cataloguing blog as a way to display and communicate the wonder of digging into these collections, especially to compensate for lack of physical exhibition space. Since then, it has blossomed into a Special Collections division-wide blog and a significant resource for information and images of our collections, for scholarly communication, and for community feedback. It is truly the communal nature of the blog, both between the various authors and with our readership, that has made Echoes such a pleasure. As of the 20th of September the blog has seen over 350,000 hits from over 130,000 individual users.

Finally, the connections that I’ve made as a curator with my colleagues amongst the stacks, working at the frontline of research support and provision, has been the most important. Often, when working with a ‘hidden’ or uncatalogued collection, you feel like Mungo Park or some other forward explorer, carving out the research landscape for subject specialists and the academy. Those initial finds in the stacks, the “holy smokes, look what I’ve found” moments, have often first been shared with the people with whom I have worked shoulder-to-shoulder. Asking a cataloguer or archivist’s to help decipher an inscription, running to the photographic archives office to ask a second opinion about a method of illustration, etc., have a way of developing a sense of togetherness, of team.

So, to all of my library colleagues, academic partners, researchers, educators, and students that I’ve met through my work here at St Andrews, I say thank you for being my friends and companions on the adventures we’ve had.

∴

So, how does a curator say goodbye to their books, their collections? You take one last, deep breath of that beautiful smell that one only finds in old libraries and archives, you turn off the lights and close the door, and then you say goodbye to the people that you’ve met along the way.

So, how does a curator say goodbye to their books, their collections? You take one last, deep breath of that beautiful smell that one only finds in old libraries and archives, you turn off the lights and close the door, and then you say goodbye to the people that you’ve met along the way.

All that’s left to say now is “adios,” and “goodbye,” and “so long, and thanks for all the books.” It’s been a fantastic ride here at St Andrews, and I’ll always hold my time here, just on the edge of beyond, very close to my heart.

–DG (Daryl Green)

Sorry to hear you're leaving!

thanks Karen, it's been a great ride here! I hope the collections keep enticing you back to St Andrews -Daryl

thank you Daryl for all that you and your colleagues have done to put St Andrews Special Collections on the map. When I was a student in St A's in the early '60's, one could only guess at what might lie buried in the Library. The students, along with all the rest of us, of today are proud to belong to a university that has such a distinguished stamp of authority: something only a really fine University Library can give. Julia Melvin

Julia, thank you for the wonderfully kind words. The University should be so proud of its library - the collections and the people that work with them are amazing. I'm glad that we've been able to open the door to our vaults, virtually, to a much wider audience. -Daryl

Oh. I envy your job !

cheers! -D

I'm sure you'll enjoy Oxford. I shall miss your occasional requests for information, even if I haven't always been able to answer them! Christine

thanks, Christine! working with this collection has been magic, as I know you are very well aware of. Do stay in touch!

Its been great having an insight into the collections. Please do another blog in the next one.

thanks, Mo. We'll see what I can do. -Daryl

Greetings from Durham University Library. It's been such a pleasure reading your posts over the years, and a privilege to be connected in this way with my alma mater. Many thanks for all your insights, and good luck in your new job.

Cheers, Christine, I hope this blog will continue to create and maintain connections! - Daryl

The best job-leaving speech I've heard. Although it's in cyberspace words, I can 'hear' your voice. Like Saloni above, how I envy you. As I am now in my 8th decade I won't be applying for the big space you will be leaving behind. But I'm sure there will be no shortage of applicants.

thank you, James, very kind, indeed. -Daryl

Best of regards. I have followed your work for some time. It will be odd not reading your posts. Cheers, Orion Sent from my iPhone >

A pleasure meeting you at St Andrews if only briefly - best of luck for the future!

Good luck Daryl (& family) in your new home, & your new workplace. Kind regards Pam Cranston (Ex libris)