USTC Conference: Gender and the Book Trades Part IV

In this fourth, and final, instalment showcasing material used in the recent USTC Conference ‘Gender and the Book Trades’, we look at items in our collections which relate to the LGBTQ+ community. Although St Andrews doesn’t actively collect material in this field (at the moment), we do have some relevant material, and works by LGBTQ+ authors.

Charlotte Charke (1713-1760) was the youngest child of actor and playwright Colley Cibber (1671-1757). An actress and transvestite, she is most famous for her memoir, A narrative of the life of Mrs. Charlotte Charke (London, 1755). She taught herself to shoot, garden, and to groom and race horses, and also studied ‘Physick’ (acting for a short while as a doctor in 1726). Her early propensity for masculine roles was prophetic of her later career as an actress renowned for playing males, and she often dressed as a man off stage. Within this guise a rich young heiress proposed to Charke (believing her to be a man), and Charke was also employed for a short time as valet, by Richard Annesley (1693-1761), 6th earl of Anglesey, a notorious rake and bigamist. Reprints of her memoir in the 19th century were usually accompanied by disapproval, but she was read with increasing enthusiasm in the late 20th century. Some scholars in the field of gender studies hailed her as a pioneer of the movement to shatter the boundaries between gender roles, although debate has raged between those who see her transvestism as a social statement and those who see it as asserting a lesbian sexual identity.

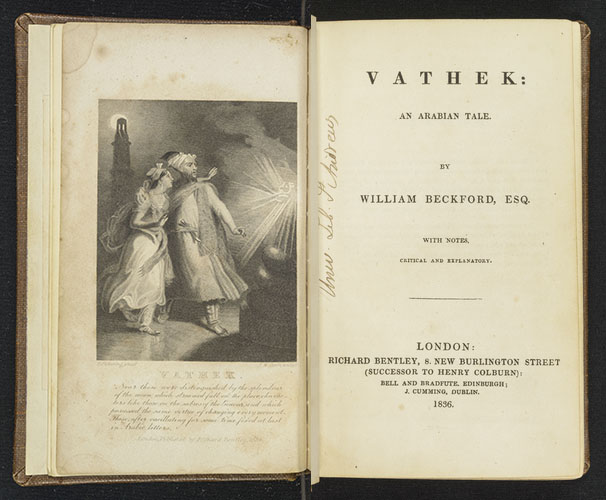

William Beckford (1760-1844) was an author and art collector, born into a family involved in the Jamaican sugar trade. As a writer, Beckford is remembered for his gothic novel Vathek, and for his travel memoir, Italy: with Sketches of Spain and Portugal. Vathek was written in French, and translated into English by the Rev. Samuel Henley (1740-1815), who had it published without Beckford’s name in 1786 as An Arabian Tale, From an Unpublished Manuscript, claiming it was composed by ‘a man of letters’ who had gathered this and other stories while in the East. Although Beckford was angered by this piracy, he appreciated Henley’s expertise as an orientalist and retained his notes in later editions. It was the 1834 English edition by the publisher Richard Bentley (1794-1871) which secured Vathek‘s success and celebrity as a classic of British Gothic fiction, alongside Horace Walpole‘s The Castle of Otranto, Ann Radcliffe‘s The Mysteries of Udolpho, and M. G. Lewis‘s The Monk.

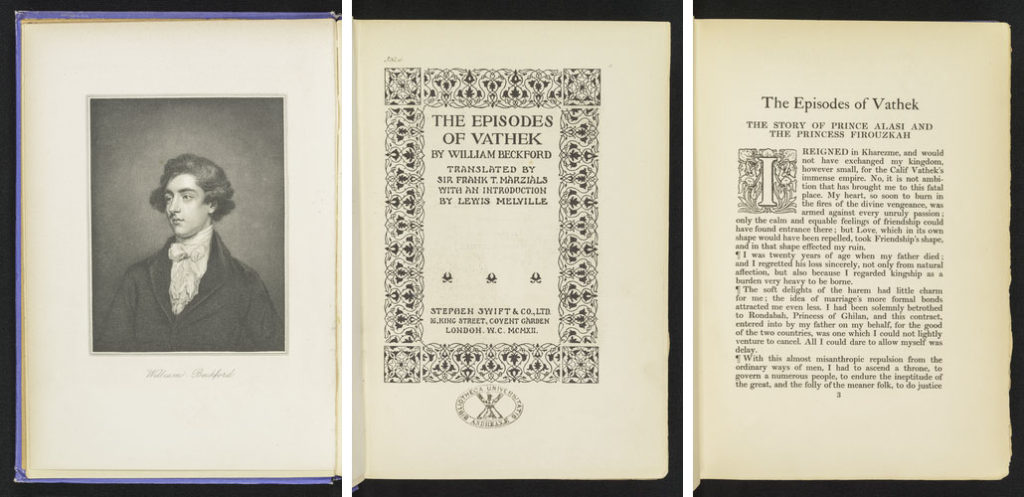

Beckford composed three ‘Episodes’ which he had originally planned to be published with Vathek, one of which, ‘The Tale of Prince Alasi’, was a lightly disguised autobiography, charting the self-destructive qualities of an obsessional homosexual – for in 1784 Beckford’s world collapsed about him in consequence of his infamous relationship with William Courtenay. Although the accusations hinted at a homosexual act, at a time when sodomy was punishable by death, no charges were ever laid against Beckford and it remains unclear whether the relationship had exceeded the bounds of youthful sentimentality. The nature of ‘Episodes’ meant they couldn’t be published independently of Vathek without risking further scandal and, having intended to include them in the corrected edition published in Paris in 1815, Beckford withdrew them. Throughout his life Beckford revised the tales, but the ‘Episodes’ vanished after his death. They were discovered by Lewis Melville (1874-1932) when he was researching the Life and Letters of William Beckford, and were translated by Sir Frank T. Marzials (1840-1912); The episodes of Vathek was published in 1912.

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) is perhaps best remembered as poet and playwright, but he was also an editor, acting in this role for Cassell’s monthly magazine The Lady’s World from November 1887 to October 1889. Upon assuming editorship of this journal he promptly renamed it The Woman’s World, in order to position it towards an emerging class of educated women, focusing more on what women thought and felt, and not exclusively on what they wore. Wilde also wrote prose works, and in July 1890 Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine published his first version of the gothic and philosophical novel The Picture of Dorian Gray.

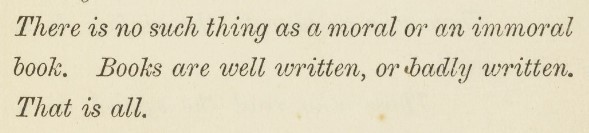

Fearing the story was indecent, prior to publication the magazine’s editor, J. M. Stoddart (1845-1921), deleted roughly five hundred words without Wilde’s knowledge. Despite that censorship, The Picture of Dorian Gray offended the moral sensibilities of British book reviewers, some of whom said that Oscar Wilde merited prosecution for violating the laws guarding public morality. Such moralistic scandal arose from the novel’s homoeroticism. Most of the criticism was, however, personal, attacking Wilde for being a hedonist with values that deviated from the conventionally accepted morality of Victorian Britain. After the initial publication of the story in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, Wilde expanded the text from 13 to 20 chapters, and obscured the homoerotic themes of the story. Despite, or possibly because of, W. H. Smith’s refusal to stock it (it being described as ‘filthy’), it was the most famous novel of its time.

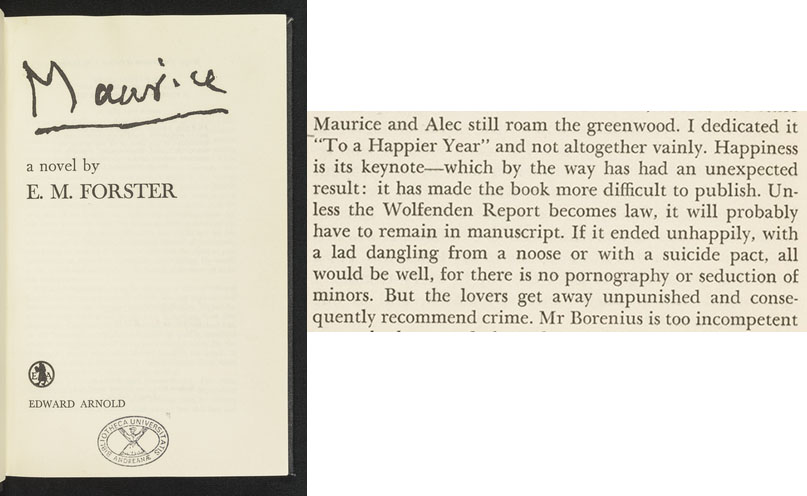

E.M. Forster (1879-1970) wrote six novels (a seventh, Arctic Summer, was never finished), many of which examine class difference and hypocrisy. His first novel, Where Angels Fear to Tread received critical acclaim, and the four subsequent novels published during his lifetime were similarly received. One novel, Maurice, was published posthumously in 1971 (St Andrews copy r PR6011.O62M2), although Forster had written it in 1913-14, revising it in 1932 and again in 1959-60. Forster was an admirer of the poet, philosopher, socialist, and early gay activist Edward Carpenter (1844-1929), and following a visit to his home in 1913 he was inspired to write Maurice. The cross-class relationship between Carpenter and his working-class partner George Merrill (1867-1928), presented a real-life model for that of Maurice and Alec Scudder. This was one of the few novels about homosexual love to have been written in the years before gay liberation, and Forster did not seek to publish it during his lifetime due to public and legal attitudes to same-sex love at the time (although it was circulated amongst his friends).

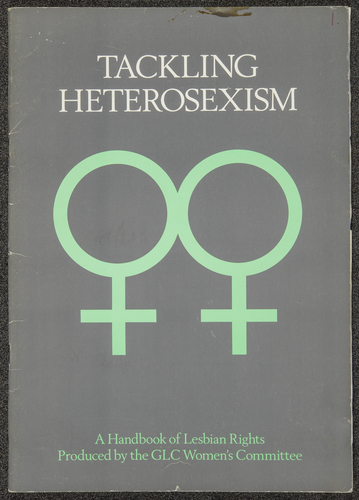

St Andrews holds the papers of Franki Raffles (1955-1994), a feminist social documentary photographer, best known for her work on the Zero Tolerance campaign. Amongst this archive we find Tackling heterosexism: a handbook of lesbian rights, which was produced by the Greater London Council Women’s Committee in 1986 as a ‘companion’ document to the Gay and Lesbian Charter. It looked in detail at the nature of the oppression and discrimination faced by lesbians and explained its impact on all women. It was felt that the booklet would go some way to filling the almost total lack of information on lesbian experience.

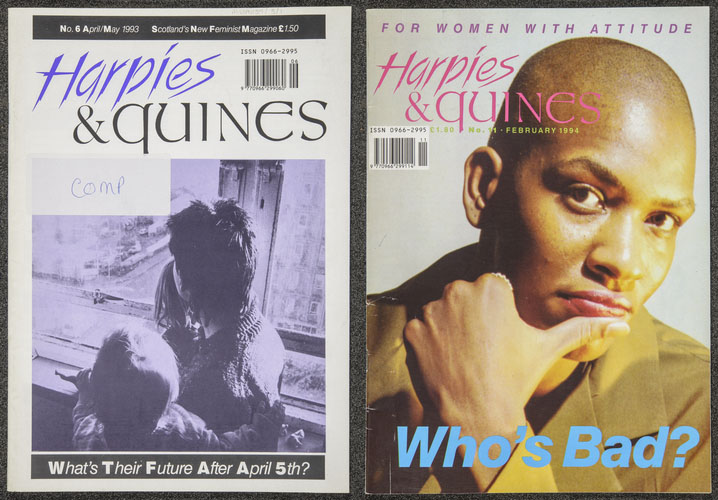

The Franki Raffles archive also has two issues of Harpies & Quines magazine (April/May 1993, Feb. 1994). This was a feminist magazine published in Scotland between 1992 and 1994, which was intended to be “used as a forum for Scottish women to discuss anything and everything under the sun”, yet in a different manner to traditional women’s magazines. It was unsuccessfully sued by Harpers and Queen, who objected to the name, but this only gave the small independent magazine the kind of front-page UK-wide publicity it could not otherwise have afforded to pay for.

This concludes our virtual showcase of some of the books shown at the USTC conference. We hope that you have enjoyed seeing some of the wide range of material held by St Andrews Libraries and Museums.

Briony Harding

Assistant Rare Books Librarian