The Kedourie Papers: Nationalism, minorities and the Middle East

In the next part of the series of blog posts about the Archive of European Intellectual Life, project archivist Miriam Buncombe, looks at the Kedourie papers, and particularly those of Elie Kedourie.

The Papers of Elie and Sylvia Kedourie begin life as an intimidatingly large collection; arriving in a motley assortment of wooden drawers, ring-binders, a laundry bag and the more conventional packing boxes, full to the brim with paper and floppy-disks. Already twice as much stuff as anticipated, shedding the occasional dead silverfish, it is hard to know where to begin. Yet as the slow process of listing and rehousing begins, relief settles in: an order emerges from the mountain of paper. This order, it eventually becomes clear, is fruit of the labours of Syliva Kedourie, who ensured the posthumous publication of her husband’s research following his sudden death in 1992.

Both scholars of the Middle East, the archival collection represents a lifetime’s partnership between Elie and Sylvia, stretched across their happy marriage and support of each other’s research; thus, as in life, their papers remain together. Still, though both worked on similar areas, each scholar nonetheless has an individual approach and an individual voice. This is perhaps most neatly represented in the tale of two expanding files: Sylvia’s file is meticulously ordered and labelled, with a series of notes carefully divided according to the alphabetical divisions of the file; Elie’s file, in contrast, has a unique order according to his own requirements, including a final division of miscellaneous extras.

Elie Kedourie (1926 –1992) and Sylvia Kedourie (1925-2016) were born into the thriving Baghdadi Jewish community of the 1920s. Both educated at the French-based Alliance Israélite Universelle schools, they grew up in a multilingual environment from the outset, a theme which runs through papers spanning French, Hebrew, Arabic and English. Following school, both Elie and Sylvia moved to the UK to undertake their undergraduate studies, at the London School of Economics and the University of Edinburgh respectively. Though England would become their home, the Iraqi Jewish community, and the gradual dispersal of this ancient community following political turbulence of the early twentieth century, would remain at the core of their personal and academic identities.

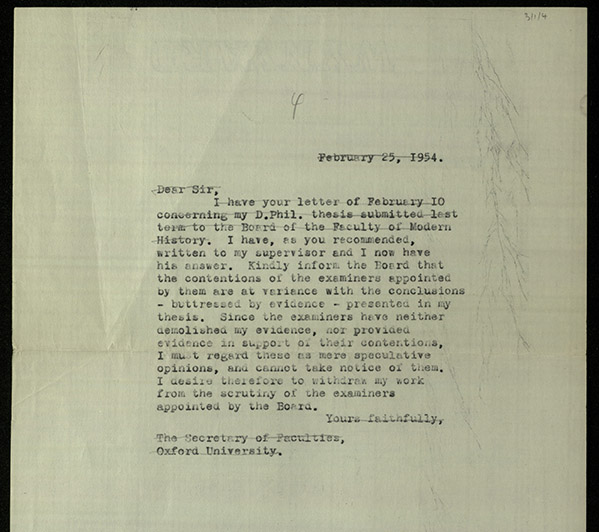

Having gained a prestigious position for doctoral research on English Policy in the Middle East at St Anthony’s College, Oxford, Elie Kedourie encountered his first hurdles in his academic progress when running up against precisely the currents of the establishment line which his thesis challenged. During his Viva examination, renowned historian H.A.R. Gibb insisted that Kedourie must make room for the argument that the social climate of the Middle East had simply been leaning towards nationalist feeling prior to any British policies in the area. As Elie outlined clearly when writing to withdraw his thesis from examination, his research was based upon a thorough study of the recorded evidence of policy and decision-making from the period, both on colonial and Arab sides, and any conclusions he had drawn would be based strictly upon such evidence as he had found; he could hold no respect for the opinions of scholars unwilling to keep to these, in his eyes, impeccable standards of historical research.

This golden standard of a return to the contemporary written record, application of nuanced awareness of the cultural context of the Middle East, and willingness to question the dominant narrative would become the cornerstone of all Elie Kedourie’s research. Offered a teaching position at the London School of Economics by Michael Oakeshott in 1953, Kedourie would remain with the LSE for the rest of his career, teaching courses including on the history of political thought and on nationalism. The exploration of the development of nationalist ideologies in the Middle East, dialogue between Western and Arabic ideas of nationalism, and political development in the region of the former Ottoman Empire from the late nineteenth century occupied the core of Elie Kedourie’s research, which he published in well-received works such as ‘Nationalism’ and ‘The Crossman Confessions’. His exploration of the topic, as in his thesis work, continued to challenge prevailing arguments regarding the destructive nature of the British Empire and inevitability of Arab nationalism, most famously in his counter to Arnold Toynbee’s arguments in ‘The Chatham House Version’.

The field of Middle Eastern studies remained strongly divided throughout Elie Kedourie’s career, with heated battles of words regularly played out in the columns of the Times Literary Supplement, Elie in a loose alliance with P.J. Vatikiotis at SOAS. So unconvinced was Kedourie with the current state of academic fora for his subject that he founded his own journal, Middle Eastern Studies, to provide a space for more varied voices in the field. This attracted article submissions from scholars across the Middle East, Israel and the U.S., though was in turn accused of being an anti-Arab clique. Correspondence with academics across the world, retained in these papers, offers a unique patchwork of evidence on trends and difficulties in research on the Middle East throughout the mid-twentieth century, from access to archival material in Jordan to difficulties of bringing Jewish and Arab scholars together at conferences. Though he considered that scholars should stay out of politics, the immediate relevance of Elie Kedourie’s subject matter to the context of the world politics of his day meant he came to work with Margaret Thatcher’s government, through the Centre for Policy Studies, providing insight on the Middle East. Yet Kedourie was strongly opposed to the changes to Higher Education proposed by Thatcher’s Conservative government, to which he ultimately became a vocal opponent.

Elie Kedourie spent his final years as a visiting fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington working on a magnum opus on conservatism. Sadly, he died unexpectedly prior to completion of this work, of which only a proposed outline remains in the collection. The threads of this topic, running through his body of research, provide a tantalising glimpse of the work that might have come from the mind of Elie Kedourie and his lifetime’s expertise on the international world of politics.

Miriam Buncombe

Project Archivist