‘The Words You Need to Be Politically Correct’: behind conservative lines in the papers of Kenneth Minogue

In the next part of the series of blog posts about the Archive of European Intellectual Life, project archivist Miriam Buncombe, focuses on the work of Kenneth Minogue.

When commemorating the life of Bill Letwin, Kenneth Minogue noted that it was always hardest to find something to write about the nice guys. Firm in his opinions, with a sharp wit and a relentless appetite for a hearty debate, the same dilemma cannot be said to arise when commenting on the life and work of Kenneth Minogue (1930 – 2013). A scholar of contemporary politics and political theory, Minogue was not one to shy away from thorny issues or to argue against prevailing currents in unfaltering terms. Centred upon an exploration of conservatism, liberalism and ideology, his research sought to understand and elucidate the impact of political approaches on the shape of contemporary society. Thoroughly conservative in outlook, Minogue applied his deep understanding of political theory to cast a sceptical eye over the increasing liberalism spreading through the socio-political landscape surrounding him.

Born in New Zealand, Kenneth Minogue had a transient childhood, growing up between New Zealand and Australia. Showing academic promise even as a boy in Auckland, where he won praise for a paper on the arrival of the American fleet in around 1938, he went on to study Arts and Law at Sydney University but left for new adventures in London shortly after. Minogue was to make his life in England, where he first married Valerie Pearson Hallett and had two children, the couple separating in 1978, subsequently marrying Beverley Cohen. Minogue nonetheless continued to consider himself an Australian, retaining friends there, writing for Antipodean publications, and regularly returning to Australia and New Zealand both for business and pleasure.

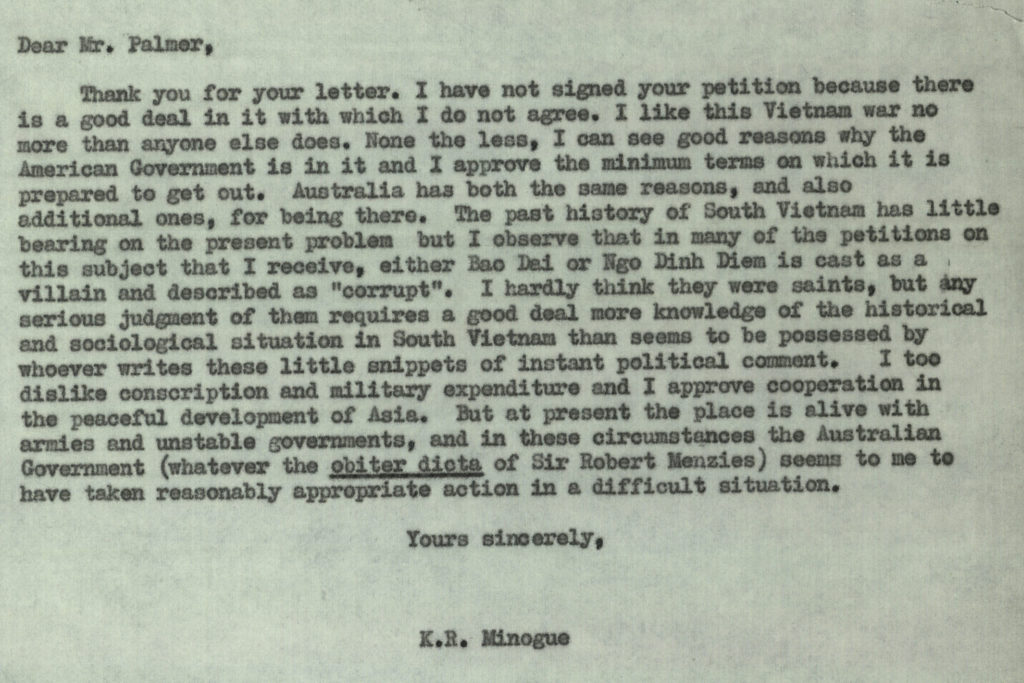

Appointed in 1956 to teach politics at the London School of Economics, where Minogue would remain for the rest of his career, he joined an influential group of conservative political thinkers under the aegis of philosopher Michael Oakeshott. This group, including Elie Kedourie and William Letwin, marked a distinct change from the left-leaning thought which had prevailed while Harold Laski had held the Chair in Political Science. Oakeshott’s nuanced approach to theory would become a defining influence on Minogue’s work, which came to include the study of Oakeshott and his philosophy. By the late 1960s, student protests dominated life at LSE, plunging Minogue into controversy as an outspoken critic of the student movement and scathing of its underlying Marxist ideology. Taking a hands-on approach, for example in aiding the dispersal of a student sit-in from the common room, Minogue became an easy target as one of the faces of a ‘capitalist’ institution and was subject of many satirical pieces in student newspaper The Beaver. The fallout of this period is captured in a fascinating series of letters between Minogue and John A. G. Griffith recalling divergent memories of the student attack on LSE’s gates in 1969. Contemporary ephemera, such as Minogue’s letter in response to a request to sign a petition against the Vietnam war (he offers a firm but detailed rejection of the premise of the petition) and humorous correspondence with The Beaver’s editorial staff immerse the reader in the atmosphere of the late 1960s at LSE.

Minogue’s sense of what was and was not the business of universities brought him into conflict several times further, for example in opposition to the proposed boycott by LSE of nations practicing Apartheid (according to Minogue, the business of politics not universities), and in his ongoing critique of equal opportunities measures (deemed unnecessary interference). This central question of what Higher Education should and should not do reappeared many times in Minogue’s work, most prominently in his extended essay ‘Defending the Universities’, but also in lectures on academia and free speech. Yet in this, as well as in his wider research, Minogue relished the chance to debate with his opponents, continuing a friendly correspondence with fellow LSE philosopher Ernest Gellner, while each scholar took delight in obliterating the other’s position in fiery journal columns. Minogue retained a keen sense of humour and did not take himself too seriously, appearing, for example, in a mock University Challenge for the Students Union and arguing his case for a ‘Trial of Karl Marx’ as part of the centenary celebrations at LSE.

Archival papers can offer the chance to step into another person’s world; in the case of Kenneth Minogue, his papers nudge open the closed doors of the conservative-minded circle surrounding him in the form of his friends in politics, business, academia and publishing. Minogue’s brand of conservative realism appealed to Margaret Thatcher, whom Minogue advised; some reports are preserved in his papers, as are invitations to dinner with the Prime Minister. For Minogue, however, the Conservative Party had peaked with Thatcher; that he had little time for subsequent Conservative Prime Ministers he makes quite clear in an acerbic letter of 2007 declining to renew his membership of the Conservative Party. Instead, Minogue was active in conservative groups including the Centre for Policy Studies, the Liberty Fund, the Euro-sceptic Bruges group and the closed libertarian group the Mont Pelerin Society, of which he became president. Through his speeches, articles and correspondence, Minogue’s papers trace an increasing sense of the marginalisation of socially conservative points of view, reflected, for instance, in responses to the idea of political correctness, feminism or systemic racism, and to proposed policies on restrictions on alcohol consumption and smoking in the UK, or the work of the Waitangi tribunal in New Zealand. Such feelings are neatly summarised in a series of Minogue’s informal typed ‘Reflections’ in which he gathered his reactions to the news and policies of each passing year. Letters to and from friends and colleagues in the UK, Canada, the U.S. and Australia, including Ray Evans (Western Mining Corporation), Owen Harries (The National Interest) and Professor Barry Cooper (University of Calgary), similarly reflect the growing frustration of conservatives who perceived their views to be undervalued in contemporary society and politics.

Clear in his own conservative philosophy, Minogue saw no value in the concept of the politically correct, resulting in a legacy of archival papers which make for fascinating – sometimes shocking – reading. This is part of the collection’s unique value; in addition to giving access to Minogue’s extensive scholarship, these papers offer an outstanding insight into the changing fortunes of conservative ideas and perspectives, which remain influential in politics today.

Miriam Buncombe

Project Archivist

This is the stuff of history, though in this case known mostly to those in academia. His thoughts on what is the the purview of universities and what is not, could well be applied to our situation in the world today, especially the United States where I live, where woke and liberal (even Marxist) policies not only are invading campuses, but have even originated there. Universities should give students the grist for thinking, developing new ideas, challenging their thinking, and never be indoctrination machines. Would that his energy and voice inform the policies we face today -- even his even-handed discourse with other, often opposing, writers, economists, and university professors.