The St Andrew manuscript ‘cutting’ and reflectance transformation imaging (RTI)

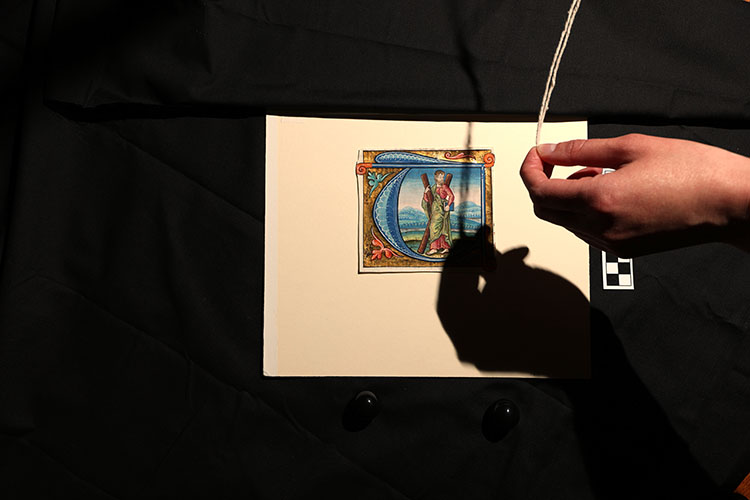

As light glimmers over the fifteenth-century illuminated initial, the calm and focused expression on the face of our university’s eponym St Andrew remains unchanged. He seems to look directly at the shadow of a measuring string and hand hovering above his frame (image 1). The string and hand were not supposed to have been in the frame for this shot—but in the rapid process of RTI (reflectance transformation imaging), sometimes mistakes happen: the process involves rapidly shooting about 45 images of a single object. Eternally patient, the depicted St Andrew does not seem to mind. The accidental photograph figures a closeness between the hand of the medieval maker, who carefully put down delicate brush strokes, the hand of the collector, who excised the initial from its original manuscript volume, and the hand of the digitiser, who measures the distance between the object and flash with the aid of a piece of string. RTI is a digital technique that uses light to illuminate that which the medieval maker created, and in one breath casts shadow around the cutting’s edge. Its moving light reminds the digital user of the glittering gold as well as the violent act of cutting. In this blog post I discuss University of St Andrews ms38667, and how reflectance transformation imaging shows the manuscript cutting in a different light.

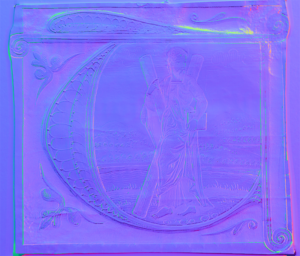

Before I discuss the manuscript cutting itself, let’s dive a little into RTI for a moment. RTI is a technique in which about 40-60 images are processed. For each shot, the camera and the object remain fixed, but the direction of the flash changes each time. In effect, you form a ‘dome’ of light around your object, with the flash lighting the object from different directions. The string provides a measuring instrument, so that the distance between the manuscript and the flash is constant throughout. The process of RTI demands the same patience and forgiveness that emanates from St Andrew. Manually, you clean up the images by removing photographs with accidental shadows before processing. A specialised app processes the ‘good’ photographs into a digital object, which can be viewed with a specialised viewer. The RTI viewer simulates the act of moving the light around (image 2). It captures the changing nature of surfaces, texture, colour and gold with the interference of light—something that is impossible to show in the static images that we are used to seeing in online environments.

The initial we are now seeing in the changing light of RTI contains a depiction of St Andrew, likely made in fifteenth-century France. The Apostle Andrew is the patron saint of Scotland, his cult having strong roots in twelfth-century Scotland. He is recognisable by his diagonal cross, or ‘saltire’, reminding us of his gruesome martyrdom. Abstracted, it forms the cross on the Scottish flag. In the French miniature, St Andrew carries a book in his left hand and steps barefoot through a landscape depicted inside the letter T. The initial was cut from its place inside a liturgical manuscript, as is clear from the plainsong musical notation, and red and black letters on the back of the cutting (image 3).

The University Library acquired the cutting in 2008, in anticipation of the university’s 600th anniversary in 2013. Currently displayed in the medieval St Andrews exhibition at the Wardlaw museum, the cutting often figures as an emblem of the University Collections.

Though not much is known about its medieval history (precisely because it was literally cut from its context), its provenance as manuscript cutting is very interesting. The cutting had been auctioned at a Sotheby’s sale on 25 April 1983 (lot 128) where a whole album of excised manuscript paintings was taken apart and separately sold. This album was owned by Daniel Burckhardt-Wildt of Basel (1759-1819), a Swiss silk manufacturer and collector who operated in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It comprised some 475 cuttings, including our St Andrew initial. Cutting manuscripts was not uncommon in this period (and the practice still persists). They were often used for study or admiration. Beholders saw the miniatures more as tiny paintings than as parts of a book. As a member of the Kunstlergesellschaft of Basel, Burckhardt bought works of art through Swiss painter and art-dealer Peter Birmann (1758-1844), who specialised in medieval miniatures. Buckhardt commissioned Birmann to assemble the album, one of the largest known albums of manuscript cutting. Whether Birmann did the cutting himself is not known. The complete album remained in the family until the 1983 sale. Margaret Connolly has figured out that the St Andrew cutting was part a group of 4 initials, of which only our initial was historiated, the others being only decorated with foliage. French antiquarian Pierre Berès (1913–2008) bought the leaf and later sold it to the University Library at St Andrews.

Now, what does RTI bring to the table when studying this cutting? Because of the nature of the RTI object, it allows us to play with light that normally remains static in digital images. This reveals surface texture but also shines a light on the changing materiality of the pigment and gold that make up the initial. The glittering gold that changes with the angle of light is the first thing that leaps out at the viewer (image 2). Gold holds special meaning in the Middle Ages. Because of its reflective qualities, it is seen as the brightest and thus the purest colour. And with its connection to light, gold was associated with the divine and seen as an embodiment of the immaterial. Moreover, gold creates lively reflections as angles of incidence continuously change—as when you are leafing through a manuscript. The gold works as a receptacle for light, if you will. And where the cutting remains static, as it is no longer part of a moving manuscript page, the golden light is re-imagined in the RTI object.

Moreover, RTI functionalities bring out the places where the gold is diminishing and where the base red ocher shows underneath. It also reveals that the gold was likely painted with so-called ‘shell-gold’. This is particularly visible in the texture that the RTI image reveals (image 4). The gold seems to lie lower than the pigment and was seemingly painted first. This becomes evident when we use the ‘Normals Visualisation’ function in the RTI viewer (image 5). The gold surrounding the St Andrew initial is likely gold powder, sometimes made by grinding gold leaf, mixed with a transparent adhesive to apply to the red ochre.

The RTI rendering of the St Andrew leaf says something not only about light, but also about shadow. The moving shadow cast by the edge of the cutting makes exceedingly clear to us that there is an edge: that the initial has been excised from its original parchment page (image 6). The shadow reveals not only the glittering light of the leaf’s medieval past, but also the violent act it underwent. This brings to light the changing function of the medieval illumination. To men like Birmann and Burckhardt, cutting the miniature meant releasing the painting from its manuscript frame, allowing the viewer to look at it and appreciate it more closely. The transformation reminds us that medieval manuscripts are not static objects: they are dynamic, they change, they move.

As the photographs in the introduction of this blog post shows, the practice of RTI is a fast-paced and fault-prone process. It is likely that during the imaging process (where a person keeps moving around the tripod to measure and hold the flash), the tripod or camera was knocked just slightly. Consequently, there is the tiniest amount of distortion in the processed images. Because the RTI builder takes all images and makes them into one single object, this movement is visible as a slight blur in the RTI object. This can be fixed by taking out the images where the movement happened or starting the imaging process again. Ironically, where RTI objects are objects in which movement of light in the most important, it is another kind of movement that has (perhaps only slightly) diminished St Andrew’s glittering frame.

Digital technologies like RTI can reveal new things about the medieval objects that we work with. It is a new lens through which we can see and study the cutting. The RTI object brings the hand of the medieval maker closer to the hand of the digitiser, finding common ground in illuminating and bringing to life the calm face of St Andrew depicted inside the initial T.

Suzette van Haaren

Additional literature

Endres, Bill. Digitizing Medieval Manuscripts: The St. Chad Gospels, Materiality, Recoveries, and Representation in 2D & 3D. Leeds: Amsterdam University Press/Arc Humanities Press, 2019.

Gage, John. ‘Colour in History: Relative and Absolute’. Art History 1, no. 1 (March 1978): 104–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.1978.tb00008.x.

Hamel, Christopher de. Cutting Up Manuscripts for Pleasure and Profit. Book Arts Press, 2002.

Hanneken, T.R. ‘Guide to Creating Spectral RTI Images’. The Jubilees Palimpsest Project, 26 September 2020 [accessed 14 April 2022].

https://web.archive.org/web/20200926223009/https://jubilees.stmarytx.edu/spectralrtiguide/.

Hindman, Sandra, Michael Camille, Nina Rowe, and Rowan Watson, eds. Manuscript Illumination in the Modern Age: Recovery and Reconstruction. Evanston: Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, 2001.

Reif, Rita. ‘AUCTIONS; Apocalypse for Sale.’ The New York Times, 25 February 1983, sec. Arts. https://www.nytimes.com/1983/02/25/arts/auctions-apocalypse-for-sale.html.

St Andrews Special Collections. ‘Illuminated Initial of St Andrew Excised from French Manuscript’. [Accessed 14 April 2022]. https://collections.st-andrews.ac.uk/item/illuminated-initial-of-st-andrew-excised-from-french-manuscript/763092.

Treharne, Elaine. Perceptions of Medieval Manuscripts: The Phenomenal Book. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Turner, Nancy. ‘Reflecting a Heavenly Light: Gold and Other Metals in Medieval and Renaissance Manuscript Illumination’. In Manuscripts in the Making, edited by Stella Panayotova and Paola Ricciardi. London/Turnhout: Harvey Miller, 2017.

This is absolutely fascinating! Thank you so much! While the manuscript cutting is horrific, I’m glad that this wonderful painting came to St. Andrews.