The 1581 Reprint of Sir David Lindsay’s A Dialogue betweene Experience and a Courtier: Evidence of the Popularity and Influence of Scottish Poetry in Elizabeth’s England

We are delighted that students on Dr Amy Blakeway’s ‘Mary Queen of Scots, France, England and Ireland’ module (MO4807) have once again submitted blog posts as part of their course. Here is the next part of a small series of blogs which reflect on the rare books with which the students engaged during their studies.

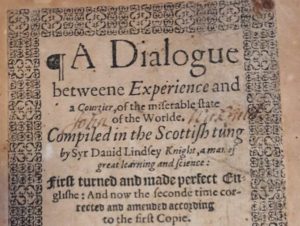

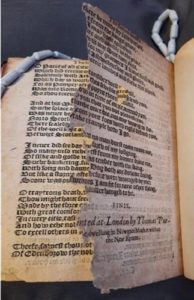

First printed anonymously in 1554, Scots poet David Lindsay’s A Dialogue betweene Experience and a Courtier of the miserable State of the Worlde, was immensely popular in England as well as Scotland because of its damning condemnation of the Catholic Church, told through a vernacular biblical history of the world. Also known as The Monarche, the copy held in the University of St Andrews’s collection was published in 1581, which marked the third time the text was printed by London-based publisher Thomas Purfoote, and was testament to its enduring popularity in England.

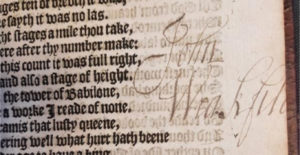

Intriguingly, there is compelling evidence of not just one, but a series of contemporary owners. The name ‘John Kirkfield’ has been carefully inscribed on the title page, and ‘John Weakfild’ has been written on five pages of verse by a strikingly different hand, as if scrawled absentmindedly while he read the book and took his notes. If the text passed through the hands of multiple individuals, it could reasonably be posited that its attraction was its bold stance and artfully constructed arguments.

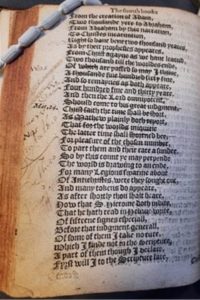

This copy bears numerous handwritten inscriptions, most of which were next to passages on papal ‘hypocrisie’. Furthermore, two pages of verse were carefully scored out by one reader at some point, indicating that this reader was perhaps a Catholic or held Catholic sympathies and was incensed by Lindsay’s assertions. Putting speculations about reader beliefs aside, the level of engagement shown proves that this was a working copy which fulfilled its intended purpose: to promote reformed ideals and reiterate the rhetoric of Catholic corruption and papal degeneracy- both popular themes in printed Tudor literature.

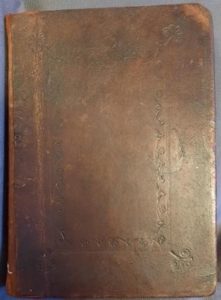

Several of the pages have been stained by food, wine, ink, and candlewax, revealing its owners could not have been careful in its handling- poring over Lindsay’s words as they ate and studied by candlelight. Its overall condition is poor, having sustained water damage, tears, and page loss, suggesting it was stored in poor conditions. Its simple leather binding dates to the seventeenth century and, given the severity of the damage sustained, this copy of The Monarche may have been kept as loose papers before then.

Initially compiled in Scots by Lindsay, the fact that this particular edition had been translated and ‘now the Seconde time corrected’ from ‘the Scottish tung’ into ‘perfect Englishe’ is an aspect of its publication which was proudly asserted in bold lettering on the title page. Enabling Purfoote to simultaneously draw attention to the ‘Otherness’ of the text, thanks to its Scottish origin, and publicise the way in which it had been repackaged to cater to an English audience, the particular appeal of a translation of Scots is interesting, as Scots would have been easily understood by any English ‘Gentleman, and such as are in aucthoritie’. We must look instead to an intellectual and cultural snobbery to explain this decision. There was a widespread understanding Scots was a crude, unintelligent language, especially in comparison to the elegant English tongue, and thus it was common for Scots texts during this time to be elevated through translation and made more worthy of English consumption.

The 1581 edition was printed in politically turbulent times. Following Catholic uprisings in Ireland and northern England, the papal reissue of Elizabeth I’s sentence of excommunication in 1580, and the arrival of the Catholic Esme Stewart in Scotland in 1579, fears of counter-reformation and even Catholic invasion of England were increasing daily. This edition was thus Purfoote’s response to heightened public uneasiness. By printing a text with a successful market-history and to which he already owned the rights, he was able to capitalise quickly and cheaply on the growing markets for both anti-Catholic writing and Scottish news and information.

The fact the Scottish poetry was chosen for circulation in response to the evolving English political and religious climates highlights that, contrary to the once-popular perception of sixteenth-century Scotland as culturally inferior to England, the two kingdoms’ literary traditions were influenced by, and reacted to, one another.

Rebecca Pollard

Printed Primary Sources

Lindsay, David, A dialogue betweene Experience and a courtier, of the miserable state of the worlde / compiled in the Scottish tung by Syr Dauid Lindsey Knight, a man of great learning and science; first turned and made perfect Englishe: and now the seconde time corrected and amended according to the first copie ; a worke very pleasant and profitable for all estates, but chiefly for gentlemen, and such as are in aucthoritie ; herevnto also are annexed certain other workes inuented by the saide knight, as may more at large appeare in a table following., (London, 1581), copy in St Andrews, University of St Andrews Library, TypBL.B81PL and a digitised copy at ESTC S108560.

Secondary Sources

Blakeway, A., ‘“Newes from Scotland” in England, 1559-1602’, Huntington Library Quarterly, 79:4, (2016), pp. 533-559.

Edington, C., Court and Renaissance Scotland: Sir David Lindsay of the Mount (1486-1555), (East Linton, 1994).

Mann, A. J., ‘The Anatomy of the Printed Book in Early Modern Scotland’, The Scottish Historical Review, 80:210, (2001), pp. 181-200.

Muller, A., The Excommunication of Elizabeth I: Faith, Politics, and Resistance in Post-Reformation England, 1570-1603, (Leiden, 2020).