The colour aniline purple – housing silk textiles from the Calvert Chemistry Collection

Bringing in collections

Incoming university collections are routinely checked for dirt, mould and insect activity before being cleaned, rehoused and shelved in the stores. Not all collection items come from suitable storage environments and this essential work ensures that dirt and harmful insect pests are not inadvertently brought into the collections. This was particularly the case with the Calvert chemistry collection – the personal archive of Dr David Calvert, a Chemistry lecturer at the university from 1972-1988, which was donated to university collections by his family in 2021. Parts of the collection were particularly dirty with surface soiling, animal hair and insect debris.

Purple silks

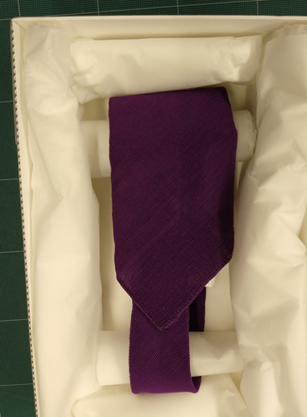

Within the archive were three silk textiles: a dyed silk tie, a sample of dyed silk and a screen-printed silk depicting a landscape scene. It is thought the textiles were created in 1956 for the centenary celebrations of William Henry Perkin’s accidental discovery of the first synthetic organic dye in 1856. The dye he discovered was known as aniline purple, mauveine, purple aniline or Perkin’s mallow. Perkins’ purple was an experimental dye and used an ingredient of coal tar which was an unwanted by-product of the distillation of coal. It is now known for its highly susceptibility to light-damage.

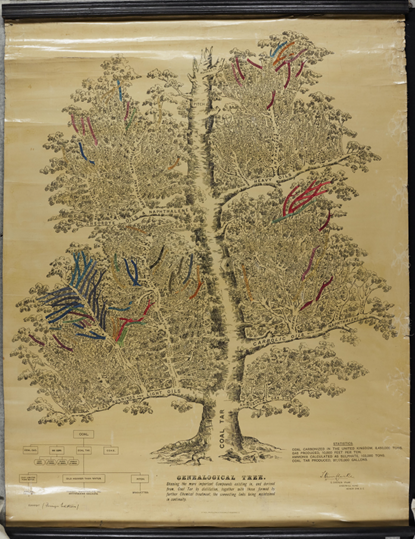

Another university collection item, the Genealogical Tree of Coal Tar, ms39084, illustrates the derivatives of coal tar. Some branches of the Coal Tar tree have been hand-coloured to present the dye colours produced from coal tar, including mauvine acetate. The Coal Tar chart was purchased by Professor Thomas Purdie, eminent chemist who established the School of Chemistry at the University of St Andrews, in February 1889. The chart was published around 30 years after Perkin’s discovery, in the late 1880’s, and demonstrates how quickly scientific understanding of coal tar derivatives moved forward in the years subsequent to his discovery.

Perkin’s scientific research and its application was so useful to chemical knowledge that he received many awards and honours in his day. Perkins is remembered each year by a prestigious chemistry prize that bears his name – The Perkin Medal. Celebrations have been held around the world by the scientific community to mark the jubilee (1906), centenary (1965) and sesquicentennial (2006) anniversaries of Perkin’s discovery.

Condition

Chemical analysis of the dyes on the Calvert textiles was not carried out. It is therefore not known how close these dyes are to Perkin’s original 1856 mauveine formula. Nonetheless the textiles are being treated as very light sensitive aniline purple objects.

The silks had been folded, retaining deep fold lines, and placed in acidic envelopes. Other than this the items are in very good condition. In considering the safest method to house the items Tuula Pardoe ACR, textile conservator at the Scottish Conservation Studio, was approached for advice. Always generous with her time and knowledge Tuula advised that folding most textiles for storage is a very bad idea. Folding causes damage in the long term because, as the fibres age and degrade they lose their elasticity. The weakened fibres can then start to break up along a creases or fold line before ultimately starting to split. The best preventive course of action is therefor to keep textiles rolled up for storage.

Protection

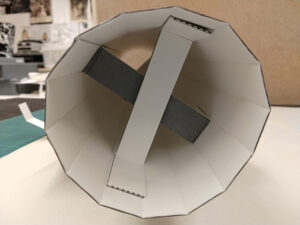

Archival-grade fluted-board was scored and folded, perpendicular to the fluting direction, to form a fourteen-sided tube. The aim was to create a strong support for the textile to be rolled onto, with a generous diameter (to avoid having to roll the fabric too tightly) while creating as few steps in the tube as possible. Interleaved layers of acid free tissue were added to the front and back of the silk before rolling. Unlike out-sized paper-based items, textiles are generally rolled with the image facing outwards. This is because textile pieces are often made of several layers. Keeping the front as the outer-most layer when rolled ensures the least possible amount of creasing in the image layer.

Tuula demonstrated an excellent technique for rolling textiles – the object is placed face down on the bench. The back (verso) layer of tissue interleave is rolled onto the tube support a few times, and then used to ‘catch’ the textile to begin rolling it onto the tube without slipping. As the textile is rolled onto the tube creases and folds can be smoothed out. When the textile has been rolled on, the front (recto) layer of tissue interleave is rolled on.

As protection against dust, light and atmospheric changes the rolled textile is housed in a custom-made box which into which the supportive tube fits tightly.

Tuula’s suggestions for improvements on the housing were to suspend the tube support within its box to avoid compression of the textile between the roll and the base of the box – particularly as the tube support is stepped. This could be achieved simply by elevating the tube off the base of the box using pieces of inert foam such as plastazote and is a wonderful suggestion for ways to use off-cuts which accumulate so quickly and cannot be recycled.

Additionally, the stepped tube could be padded using inert cushioning materials such as polyester felt or unbleached cotton curtain lining, secured by sewing, or by a layer of tissue paper – which would have the additional benefit of preventing fibre transfer from the cushioning layer to the object.

The dyed silk tie was housed in in a custom box padded out with acid-free tissue. To avoid creases, the folds were supported by ‘tubes’ of tissue to create a more rounded shape rather than a sharp fold.

Textiles are unusual in the Rare Book and Archive collections. Among the exceptions are the textile bindings of the Wardlaw Bible and bag (Bib BS170.C40), Psalms and New Testament 1627 in an embroidered dos-a-dos binding (Bib BS2085.C27) and an embroidered cover of the common place book of Catherine Fletcher (ms37489).

Similar to the preservation needs of book and paper collection items, textiles require protection from light, excessive moisture and heat, insect pests and dust as well as care in handling.

Continued legacy

Working with the silks has been an enriching collaborative experience and an exploration into the fascinating early history of a synthetic dye which transformed the world of fashion and influenced everything from food and photography to medicine and military research.

The cleaned and housed Calvert collection will be catalogued and made accessible in the reading room for students, researchers and academics to make further discoveries in the history of science.

Trina Foote

Collections Care Assistant

Erica Kotze

Conservator

There is another and rather amusing tale that brings Perkins' aniline dye and St Andrews together. At the time of the Quincentenary Celebrations of the University, some emphasis was placed on St Andrews' standing as a seat of scientific achievement. The invited distinguished scientific guests were shared out between Professor (emeritus) Purdie and Professor Irvine. The Irvines were given Professor WH Perkin, the younger, and his wife to look after. Jim Irvine went down to the Station to meet them, and as he approached them, he could hear Mrs Perkin say to her husband, 'Oh kind Professor Irvine has sent his son down to meet us'. 'That's not his son', Professor Perkin replied. 'That's Professor Irvine.' The crystallographer, Professor Pope, and his wife were also the Irvines' guests and before the Perkins arrived, Mrs Pope made Mabel Irvine laugh by warning her that Mrs Perkin was in the habit of wearing an evening dress dyed mauve by the application of her late father-in-law's famous dye. The popularity of William Perkins' mauve dye is thought to have been encouraged by the widowed Queen Victoria who found mauve a welcome alternative to black.

An amusing anecdote linking WH Perkin's aniline dye and St Andrews is associated with the Quincentenary celebrations of the University. Some emphasis was placed on St Andrews being noted for scientific achievement, and the chemical distinguished guests were shared out between Professor (emeritus) Purdie and Professor Irvine. The Irvines were to look after the crystallographer Professor Pope and his wife, and Professor WH Perkin, the younger, and his wife. Jim Irvine went down to the station to meet the Perkins, and as he approached them he could hear Mrs Pope say to her husband, 'Oh kind Professor Irvine has sent his son down to meet us'. 'That's not his son' Professor Perkin laughingly replied. 'That's Professor Irvine.' In the meantime Mrs Irvine was giving tea to Mrs Pope, who amused her by warning her that Mrs Perkin was in the habit of wearing an evening dress dyed mauve by her late father-in-law's aniline dye. It is often said the the popularity of the mauve dye derived from the widowed Queen Victoria who welcomed it as an alternative to black for mourning clothes.

I apologise for giving you two almost identical posts! I thought that the first had not gone through!

Dear Julia, no need to apologise. Thanks for your comment and interesting anecdote about Professor Irvine and the Perkins.

A really great post: I love your housing solutions, and will definitely be taking those on board for the collection at the University of Reading. Thanks so much for sharing this. A fantastically simple but effective solution to the endless problem of getting tubes that are sufficiently wide in diameter but don't weigh too much. I wonder if polyester wadding, stitched on through the tube and covered by an unbleached cotton textile would be a good padding? I also love the coal tree manuscript - is there a copy online or available?

Hello Victoria, Thank you for your comment and questions. It's good to know you found the post helpful, and it's lovely to engage with readers of the blog. Your suggestion of a method to pad the tube sounds like a great solution to provide cushioning and a smooth surface. I would be very interested to see your refinements of our housing on examples from University of Reading, if you are willing to share them in time.