Notarial marks in the St Andrews burgh charters

Scottish History PhD candidate Kate McGregor has been has been working for the past year as a Research Assistant on a project investigating notaries and their networks in late medieval St Andrews, supported by generous funding from the St Andrews Local History Foundation, administered by the Burnwynd Trust. In this her second blog post on the project she details the fascinating, yet largely understudied, notarial marks contained in the Burgh charters of St Andrews.

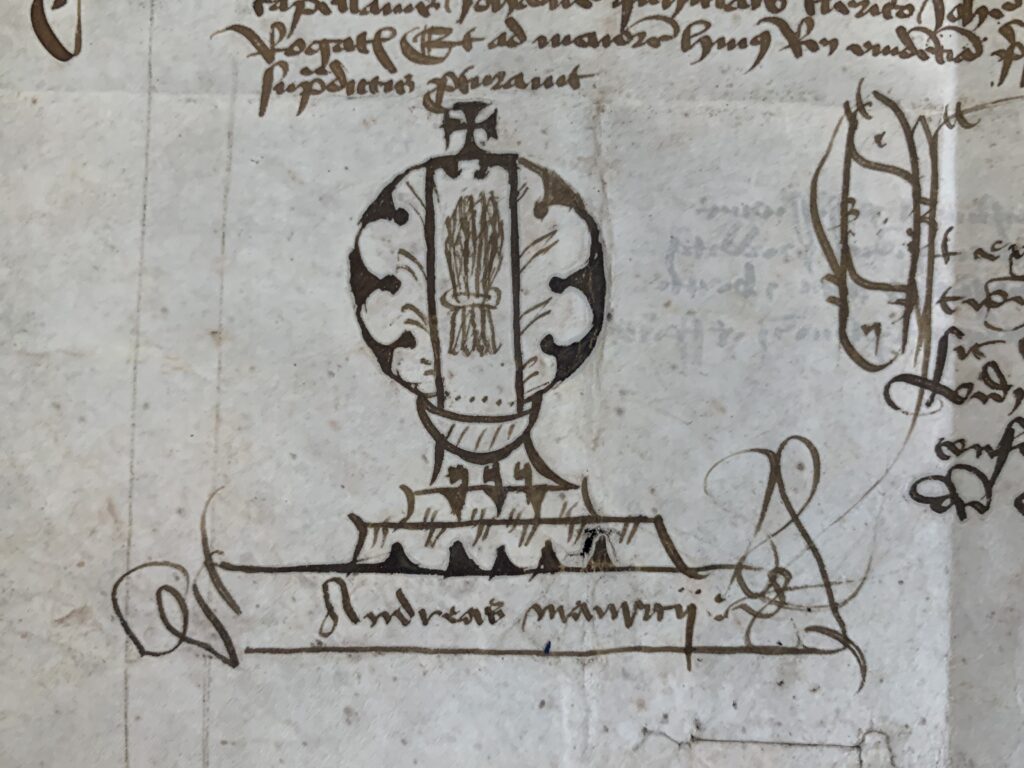

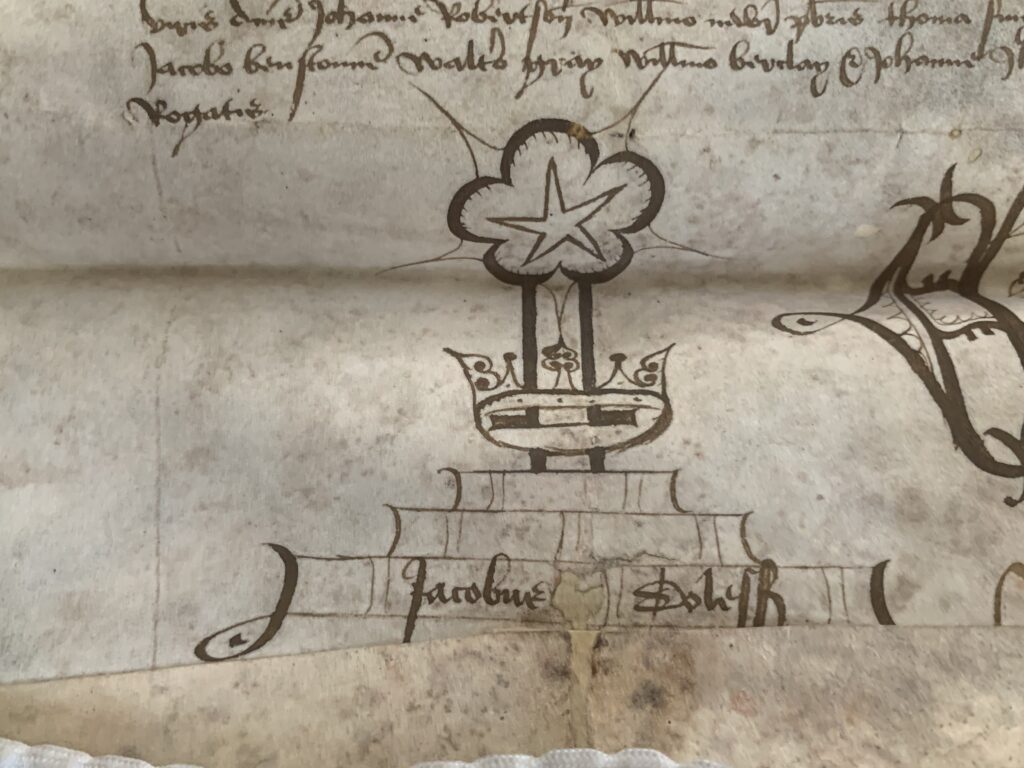

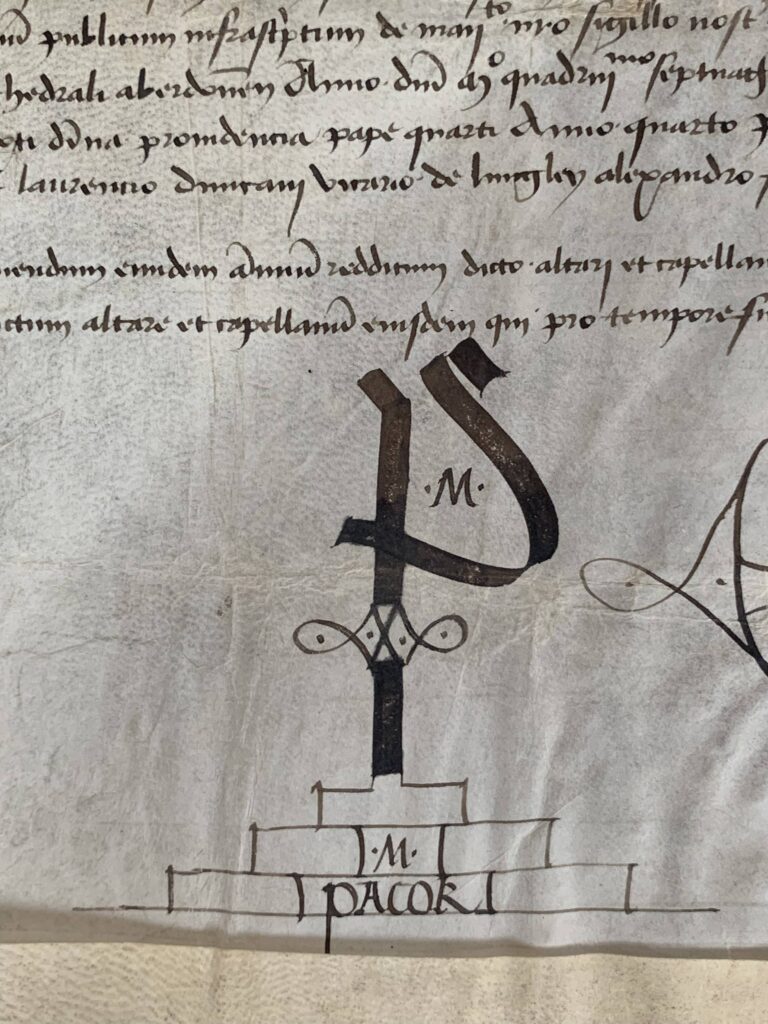

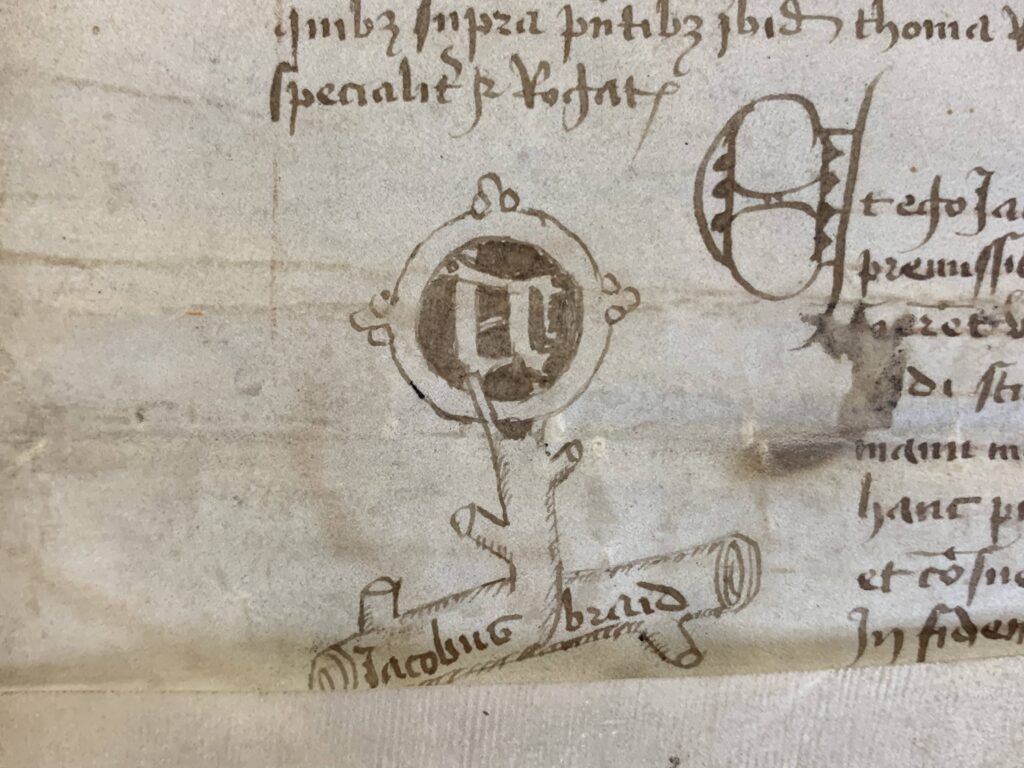

In the bottom left-hand corner of nearly every notarial instrument in the Burgh Records of St Andrews there sits a peculiar small drawing, often no more than five centimetres in height. These instruments, as the previous blog post of this series has outlined, were most often recording property transfers authenticated by a notary – a legal position with particular trust and prestige in late medieval Scottish society.

These small drawings, so intriguing and so understudied are notarial marks or signs. Within these instruments these marks served a dual purpose – to authenticate a document and visually to display the identity of the notary who created the document. In legitimising the transfer of property notarial marks were much like a seal or a signature.

As part of my research project on notaries and their networks in medieval St Andrews, I continued work on constructing a register of notarial marks, which could be the basis of an online database of notarial marks in medieval Scotland. This had been begun by the pilot project funded by a Barrow award from the Scottish Medievalists. Such a database could help historians and archivists identify notarial marks and allow us to formulate a more nuanced understanding of patterns, of change over time, and of notarial practice itself.

Such marks were used by notaries across the British Isles in the medieval period and were rooted in ecclesiastical tradition, since a notary practiced with authority granted by a church diocese or by imperial or royal authority. Fourteenth century examples of English notarial marks are held in the Borthwick Institute of the University of York, and they show remarkable similarities with the Scottish notarial marks shown below. Further extant copies of documents with notarial marks are held in Balliol College, Oxford, and are likewise similar in their construction (Notarial Signs from the York Archiepiscopal Records, ed. J. S. Purvis (York, 1957); ‘The UK and Ireland Notarial Forum’ <https://www.ukinf.org.uk/roleinscotland.html). There are also examples of such marks in medieval France and the city-states within the medieval Italian peninsula (The Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York [York Bor], Cause Papers in the Diocesan Courts of the Archbishopric of York, 1300-1858, CP.E.130; York Bor, CP.E.178; Balliol College, University of Oxford [Oxf BA], E.7.9; Oxf BA, D.3.3.).

These marks were fundamentally an expression of identity, often displaying the name of the notary, as well as distinctive artistic features which we must assume held some personal significance for the notary themselves. Marks – unlike seals, and more like signatures –were free-drawn in ink. Although, they were considerably more intricate than a signature and presumably would have taken a substantial time to complete.

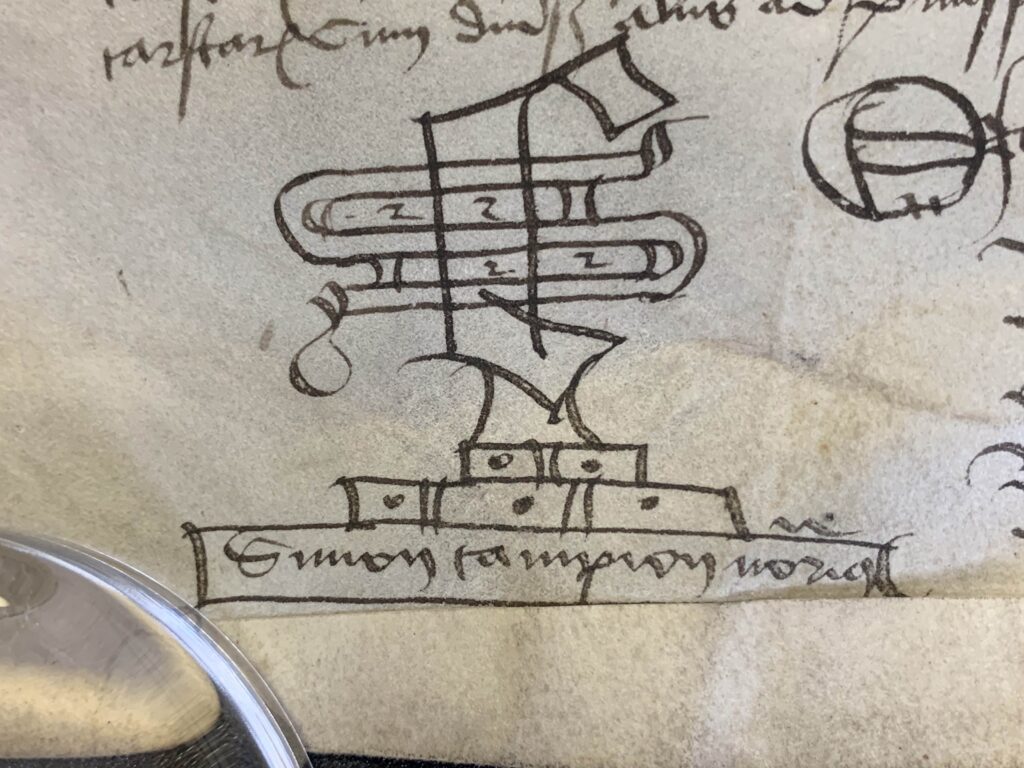

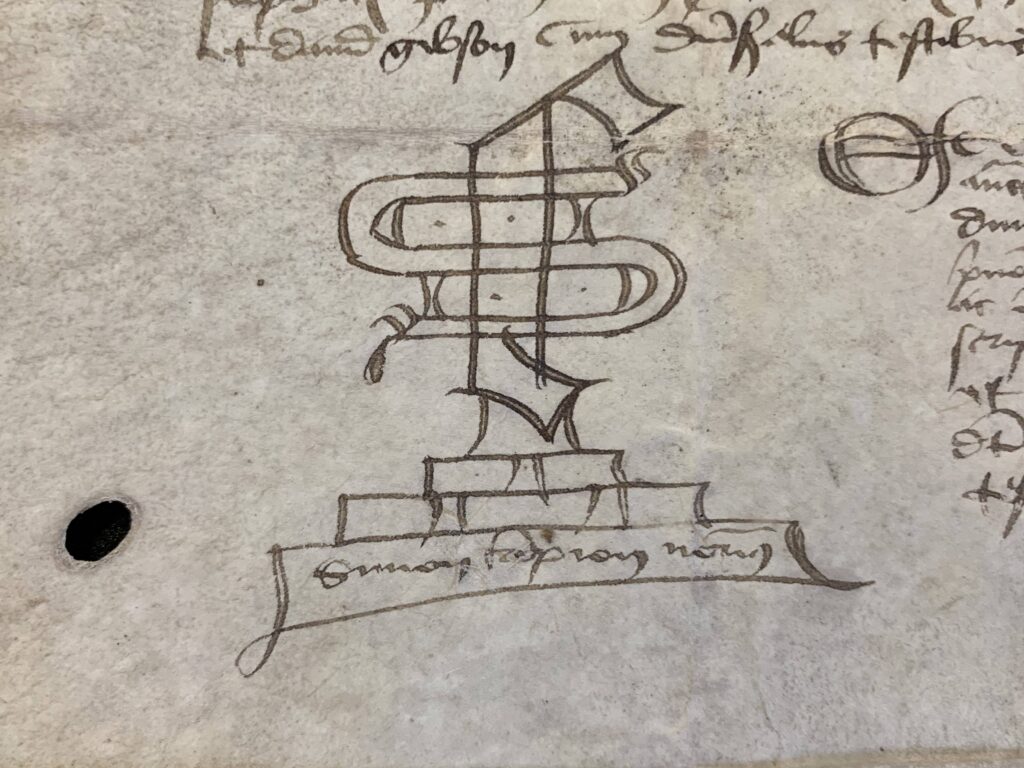

The intricacies of their design perhaps also served to prevent forgeries, however, it seems more likely that such flourishes were stylistic, rather than substantive. Most notarial marks had three tiers, or rectangular oblongs, at their base. These tiers might be supposed to be emblematic of books stacked on top of one and other, to signify learning and authority – a suggestion made by Alexa Zildjian, Senior Libraries Assistant (Reading Room) at University Collections.

The lowest rectangle generally contained the name of the notary, in its Latin form, and some indication of their position as a ‘notary public’. The top half of the marks are highly variable. Some marks showed images of nature, a sheaf of corn or a tree branch. One even contained a crown! Others religious images, such as the cross, or instead the majuscule initials of the notary, interlaced. There were varieties of shading within the marks, with block shading and criss-crossed shading, that gave a three-dimensional aspect to the signs. Rachel Hart adds: “Pre-Reformation notarial marks generally mirror the shape of a monstrance, a vessel used in worship to display the consecrated host at the Eucharist. This has a headpiece on a tall upright which is rooted in a base wide enough to balance the object while in use.”

As well as considering the plethora of fascinating notarial marks across B65/23 it is also pertinent to consider variation, and uniformity, of a notary’s mark across different instruments and extant records.

The survivability of instruments notarised by Simon Campion makes his notarial mark an excellent case study for comparing variations of a notary’s mark across different documents. Considering, all notarial marks were hand drawn the uniformity is remarkable.

Kate McGregor is a second-year PhD candidate in Scottish History at the University of St Andrews, supervised by Professor Michael Brown and Dr Amy Blakeway, and fully funded by the Ewan & Christine Brown Postgraduate Scholarship in the Arts and Humanities. Her PhD thesis explores foreign policy during the adult reign of James V, King of Scots, 1528-1542. She completed her undergraduate degree at St Andrews and her MPhil at Trinity Hall, Cambridge. Follow Kate on Twitter @ks_mcgregor for even more history content!

I am currently writing a paper on the Notaries active in the Northern Dioceses of Scotland up to the Reformation (Moray, Ross, Caithness and Aberdeen).. Far from complete but you may like a copy when it is finished? Early Church in Northern Scotland (ECNS) [email protected]